You are here

Species

West Nile virus Heinz et al., 2000

IUCN

NCBI

EOL Text

West Nile virus (WNV) is a mosquito-borne zoonotic arbovirus belonging to the genus Flavivirus in the family Flaviviridae. This flavivirus is found in temperate and tropical regions of the world. It was first identified in the West Nile subregion in the East African nation of Uganda in 1937. Prior to the mid 1990s, WNV disease occurred only sporadically and was considered a minor risk for humans, until an outbreak in Algeria in 1994, with cases of WNV-caused encephalitis, and the first large outbreak in Romania in 1996, with a high number of cases with neuroinvasive disease. WNV has now spread globally, with the first case in the Western Hemisphere being identified in New York City in 1999 (Nash et al. 2001); over the next 5 years, the virus spread across the continental United States, north into Canada, and southward into the Caribbean Islands and Latin America. WNV also spread to Europe, beyond the Mediterranean Basin [a new strain of the virus was recently (2012) identified in Italy]. WNV is now considered to be an endemic pathogen in Africa, Asia, Australia, the Middle East, Europe and in the United States, which in 2012 has experienced one of its worst epidemics.

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Text from Wikipedia |

| Source | http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=West_Nile_virus&oldid=514558420 |

Tropical and subtropical regions are common habitats for West Nile virus. WNV thrives in areas where there are significant mosquito densities. However, it is possible for WNV to survive in areas deficient in mosquitos if there are other organisms that can serve. Warm, humid environments are favorable for mosquito breeding and transmission of WNV (Jiménez-Clavero, 2012). Tropical storms can also produce environments that are conducive for the development of dense mosquito populations. After Hurricane Katrina, there was a significant increase in the number of WNV in the gulf area. Mosquitos were able to breed in the flooded swimming pools and voids in fallen and rotting trees. These areas provided excellent mosquito larval habitats (Caillouët et al., 2008). WNV simply thrives where mosquitos thrive due to the mosquitos’ role as the primary vector.

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Ashley Stelling, Ashley Stelling |

| Source | No source database. |

Rossi also provides a very in-depth description of the flavivirus life cycle. The life cycle of a flavivirus, such as West Nile virus, is characterized by four main stages. These stages include attachment/entry, translation, replication, and assembly/egress. WNV enters the host’s cells through receptor-mediated endocytosis. At this time, the receptor for WNV is unknown, but some potential receptors include Integrin alpha-v beta-3 and DC-SIGN. The endosomal compartment is acidified and this causes the E protein to undergo a conformational change. This change of the E protein results in the fusion of the endosomal and viral membranes. The virus nucleocapsid is then released into the cytoplasm of the cell. The host cell then translates the viral RNA, and the WNV polyprotein is formed. Through the formation of this protein, extensive damage to the host cell’s endoplasmic reticulum occurs. The ER is greatly expanded and modified in order to accommodate WNV. The replicated genome is then packaged in virions. These virions then travel along the ER-Golgi secretion pathway, similar to normal products of the host cell. The new WNV cells produced through this process then exit the host cell through exocytosis (Rossi, 2010).

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Ashley Stelling, Ashley Stelling |

| Source | No source database. |

Rossi provides a detailed description of the molecular biology of West Nile virus. West Nile virus (WNV) is a positive-stranded RNA virus. An envelope surrounds the cell. Within the envelope, an icosahedral capsid provides protection for the nucleic acid of the virus. WNV has an approximately 11 kilobase genome, and this genome encodes a single open reading frame, meaning it does not contain any stop codons. The open reading frame is bordered by 3’ and 5’ untranslated regions (UTR). Upon translation, a 3000 amino acid polyprotein is formed. Both viral and cellular proteases then cleave this polyprotein into ten individual proteins. These proteins vary in function. Three are structural components. The other seven are nonstructural proteins that are necessary for genome replication. Each of these seven proteins has a specific function in the replication of the genome (Rossi et al., 2010).

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Ashley Stelling, Ashley Stelling |

| Source | No source database. |

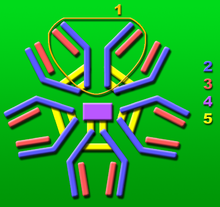

The primary risk associated with West Nile virus is its role as a pathogen in varying species of animal. The most commonly affected organisms include birds, horses, and humans. Hayes describes the clinical manifestations of WNV in great detail. WNV enters its host through the site of inoculation. From there, the virus works its way to the lymph nodes and enters the bloodstream. WNV infects neurons in the spinal cord, brainstem, and the gray matter of the brain. This infection of the brain does not always result in the manifestation of symptoms. Approximately 80% of the infections recorded in humans have been asymptomatic. However, this infection can result in serious disease and possibly death. WNV can cause West Nile fever (WNF) in its host. The symptoms of WNF include fever, malaise, headache, muscle pain, fatigue, and weakness. In more severe cases, macular rashes and gastrointestinal symptoms have been reported. Neuroinvasive disease can develop in the most severe cases. However, less than 1% of all recorded human WNV cases have resulted in neuroinvasive disease. Neuroinvasion can result in encephalitis, meningitis, paralysis, and even death. The image below shows various features of WNV in human tissues (Hayes et al., 2005).

“Histopathologic features of West Nile virus (WNV) in human tissues. Panels A and B show inflammation, microglial nodules, and variable necrosis that occur during WNV encephalitis; panel C shows WNC antigen (red) in neurons and neuronal processes using an immunohistochemical stain; panel D is an electron micrograph of WNV in the endoplasmic reticulum of a nerve cell (arrow). Bar = 100 nm.”

Figure 2 (Hayes et al. 2005)

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Ashley Stelling, Ashley Stelling |

| Source | No source database. |

| West Nile fever | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | A92.3 |

| ICD-9 | 066.4 |

| DiseasesDB | 30025 |

| MedlinePlus | 007186 |

| Patient UK | West Nile virus |

| MeSH | D014901 |

West Nile virus (WNV) is a mosquito-borne zoonotic arbovirus belonging to the genus Flavivirus in the family Flaviviridae. This flavivirus is found in temperate and tropical regions of the world. It was first identified in the West Nile subregion in the East African nation of Uganda in 1937. Prior to the mid-1990s, WNV disease occurred only sporadically and was considered a minor risk for humans, until an outbreak in Algeria in 1994, with cases of WNV-caused encephalitis, and the first large outbreak in Romania in 1996, with a high number of cases with neuroinvasive disease. WNV has now spread globally, with the first case in the Western Hemisphere being identified in New York City in 1999;[1] over the next five years, the virus spread across the continental United States, north into Canada, and southward into the Caribbean islands and Latin America. WNV also spread to Europe, beyond the Mediterranean Basin, and a new strain of the virus was identified in Italy in 2012.[2] WNV is now considered to be an endemic pathogen in Africa, Asia, Australia, the Middle East, Europe and in the United States, which in 2012 has experienced one of its worst epidemics. In 2012, WNV killed 286 people in the United States, with the state of Texas being hard hit by this virus,[3] making the year the deadliest on record for the United States.[4]

The main mode of WNV transmission is via various species of mosquitoes, which are the prime vector, with birds being the most commonly infected animal and serving as the prime reservoir host—especially passerines, which are of the largest order of birds, Passeriformes. WNV has been found in various species of ticks, but current research suggests they are not important vectors of the virus. WNV also infects various mammal species, including humans, and has been identified in reptilian species, including alligators and crocodiles, and also in amphibians. Not all animal species that are susceptible to WNV infection, including humans, and not all bird species develop sufficient viral levels to transmit the disease to uninfected mosquitoes, and are thus not considered major factors in WNV transmission.[5][6]

Approximately 80% of West Nile virus infections in humans are subclinical, which cause no symptoms.[7] In the cases where symptoms do occur—termed West Nile fever in cases without neurological disease—the time from infection to the appearance of symptoms (incubation period) is typically between 2 and 15 days. Symptoms may include fever, headaches, fatigue, muscle pain or aches (myalgias), malaise, nausea, anorexia, vomiting, and rash. Less than 1% of the cases are severe and result in neurological disease when the central nervous system is affected. People of advanced age, the very young, or those with immunosuppression, either medically induced, such as those taking immunosupressive drugs, or due to a pre-existing medical condition such as HIV infection, are most susceptible. The specific neurological diseases that may occur are West Nile encephalitis, which causes inflammation of the brain, West Nile meningitis, which causes inflammation of the meninges, which are the protective membranes that cover the brain and spinal cord, West Nile meningoencephalitis, which causes inflammation of the brain and also the meninges surrounding it, and West Nile poliomyelitis—spinal cord inflammation, which results in a syndrome similar to polio, which may cause acute flaccid paralysis.

Currently, no vaccine against WNV infection is available. The best method to reduce the rates of WNV infection is mosquito control on the part of municipalities, businesses and individual citizens to reduce breeding populations of mosquitoes in public, commercial and private areas via various means including eliminating standing pools of water where mosquitoes breed, such as in old tires, buckets, unused swimming pools, etc. On an individual basis, the use of personal protective measures to avoid being bitten by an infected mosquito, via the use of mosquito repellent, window screens, avoiding areas where mosquitoes are more prone to congregate, such as near marshes, areas with heavy vegetation etc., and being more vigilant from dusk to dawn when mosquitoes are most active offers the best defense. In the event of being bitten by an infected mosquito, familiarity of the symptoms of WNV on the part of laypersons, physicians and allied health professions affords the best chance of receiving timely medical treatment, which may aid in reducing associated possible complications and also appropriate palliative care.

Contents

Signs and symptoms[edit]

The incubation period for WNV—the amount of time from infection to symptom onset—is typically from between 2 and 15 days. Headache can be a prominent symptom of WNV fever, meningitis, encephalitis, meningoencephalitis, and it may or may not be present in poliomyelytis-like syndrome. Thus, headache is not a useful indicator of neuroinvasive disease.(CDC)

- West Nile fever (WNF), which occurs in 20 percent of cases, is a febrile syndrome that causes flu-like symptoms.[8] Most characterizations of WNF generally describe it as a mild, acute syndrome lasting 3 to 6 days after symptom onset. Systematic follow-up studies of patients with WNF have not been done, so this information is largely anecdotal. In addition to a high fever, headache, chills, excessive sweating, weakness, fatigue, swollen lymph nodes, drowsiness, pain in the joints and flu-like symptoms. Gastrointestinal symptoms that may occur include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and diarrhea. Fewer than one-third of patients develop a rash.

- West Nile neuroinvasive disease (WNND), which occurs in less than 1 percent of cases, is when the virus infects the central nervous system resulting in meningitis, encephalitis, meningoencephalitis or a poliomyelitis-like syndrome.[9] Many patients with WNND have normal neuroimaging studies, although abnormalities may be present in various cerebral areas including the basal ganglia, thalamus, cerebellum, and brainstem.[9]

- West Nile virus encephalitis (WNE) is the most common neuroinvasive manifestation of WNND. WNE presents with similar symptoms to other viral encephalitis with fever, headaches, and altered mental status. A prominent finding in WNE is muscular weakness (30 to 50 percent of patients with encephalitis), often with lower motor neuron symptoms, flaccid paralysis, and hyporeflexia with no sensory abnormalities.[10][11]

- West Nile meningitis (WNM) usually involves fever, headache, and stiff neck. Pleocytosis, an increase of white blood cells in cerebrospinal fluid, is also present. Changes in consciousness are not usually seen and are mild when present.

- West Nile meningoencephalitis is inflammation of both the brain (encephalitis) and meninges (meningitis).

- West Nile poliomyelitis (WNP), an acute flaccid paralysis syndrome associated with WNV infection, is less common than WNM or WNE. This syndrome is generally characterized by the acute onset of asymmetric limb weakness or paralysis in the absence of sensory loss. Pain sometimes precedes the paralysis. The paralysis can occur in the absence of fever, headache, or other common symptoms associated with WNV infection. Involvement of respiratory muscles, leading to acute respiratory failure, can sometimes occur.

- West-Nile reversible paralysis,. Like WNP, the weakness or paralysis is asymmetric.[12] Reported cases have been noted to have an initial preservation of deep tendon reflexes, which is not expected for a pure anterior horn involvement.[12] Disconnect of upper motor neuron influences on the anterior horn cells possibly by myelitis or glutamate excitotoxicity have been suggested as mechanisms.[12] The prognosis for recovery is excellent.

- Nonneurologic complications of WNV infection that may rarely occur include fulminant hepatitis, pancreatitis,[13]myocarditis, rhabdomyolysis,[14]orchitis,[15]nephritis, optic neuritis[16] and cardiac dysrhythmias and hemorrhagic fever with coagulopathy.[17]Chorioretinitis may also be more common than previously thought.[18]

- Cutaneous manifestations specifically rashes, are not uncommon in WNV-infected patients; however, there is a paucity of detailed descriptions in case reports and there are few clinical images widely available. Punctate erythematous (?), macular, and papular eruptions, most pronounced on the extremities have been observed in WNV cases and in some cases histopathologic findings have shown a sparse superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, a manifestation commonly seen in viral exanthems (?). A literature review provides support that this punctate rash is a common cutaneous presentation of WNV infection. (Anderson RC et al.)[19]

Virology[edit]

West Nile virus life cycle. After binding and uptake, the virion envelope fuses with cellular membranes, followed by uncoating of the nucleocapsid and release of the RNA genome into the cytoplasm. The viral genome serves as messenger RNA (mRNA) for translation of all viral proteins and as template during RNA replication. Copies are subsequently packaged within new virus particles that are transported in vesicles to the cell membrane.

WNV is one of the Japanese encephalitis antigenic serocomplex of viruses. Image reconstructions and cryoelectron microscopy reveal a 45–50 nm virion covered with a relatively smooth protein surface. This structure is similar to the dengue fever virus; both belong to the genus Flavivirus within the family Flaviviridae. The genetic material of WNV is a positive-sense, single strand of RNA, which is between 11,000 and 12,000 nucleotides long; these genes encode seven nonstructural proteins and three structural proteins. The RNA strand is held within a nucleocapsid formed from 12-kDa protein blocks; the capsid is contained within a host-derived membrane altered by two viral glycoproteins.

Phylogeny[edit]

Phylogenetic tree of West Nile viruses based on sequencing of the envelope gene during complete genome sequencing of the virus[20]

Studies of phylogenetic lineages determined WNV emerged as a distinct virus around 1000 years ago.[21] This initial virus developed into two distinct lineages, lineage 1 and its multiple profiles is the source of the epidemic transmission in Africa and throughout the world. Lineage 2 was considered an Africa zoonosis. However, in 2008, lineage 2, previously only seen in horses in sub-Saharan Africa and Madagascar, began to appear in horses in Europe, where the first known outbreak affected 18 animals in Hungary in 2008.[22] Lineage 1 West Nile virus was detected in South Africa in 2010 in a mare and her aborted fetus; previously, only lineage 2 West Nile virus had been detected in horses and humans in South Africa.[23] A 2007 fatal case in a killer whale in Texas broadened the known host range of West Nile virus to include cetaceans.[24]

The United States virus was very closely related to a lineage 1 strain found in Israel in 1998. Since the first North American cases in 1999, the virus has been reported throughout the United States, Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean, and Central America. There have been human cases and equine cases, and many birds are infected. The Barbary macaque, Macaca sylvanus, was the first nonhuman primate to contract WNV.[25] Both the United States and Israeli strains are marked by high mortality rates in infected avian populations; the presence of dead birds—especially Corvidae—can be an early indicator of the arrival of the virus.

Transmission[edit]

West Nile virus maintains itself in nature by cycling between mosquitoes in the genus Culex and certain species of birds. A mosquito (the vector) bites an uninfected bird (the host), the virus amplifies within the bird, an uninfected mosquito bites the bird and is in turn infected. Other species such as humans and horses are incidental infections, because the virus does not amplify well within these species and they are considered dead-end hosts.

West Nile virus (WNV) is transmitted through female mosquitoes, which are the prime vectors of the virus. Only females feed on blood, and different species take a blood meal's from different types of vertebrate hosts. The important mosquito vectors vary according to geographical area; in the United States, Culex pipiens (Eastern United States, and urban and residential areas of the United States north of 36-39°N), Culex tarsalis (Midwest and West), and Culex quinquefasciatus (Southeast) are the main vector species.[26]

The mosquito species that are most frequently infected with WNV feed primarily on birds.[27] Mosquitoes show further selectivity, exhibiting preference for different species of birds. In the United States, WNV mosquito vectors feed on members of the Corvidae and thrush family more often that would be expected from their abundance,.[28] Among the preferred species within these families are the American crow, a corvid, and the American robin (Turdus migratorius), a thrush.[28]

The proboscis of a female mosquito—here a southern house mosquito (Culex quinquefasciatus)—pierces the epidermis and dermis to allow it to feed on human blood from a capillary: this one is almost fully tumescent. The mosquito injects saliva, which contains an anesthetic, and an anticoagulant into the puncture wound, and in infected mosquitoes, West Nile virus.

Some species of birds develop sufficient viral levels (>~104.2 log PFU/ml;[29]) after being infected to transmit the infection to biting mosquitoes that in turn go on to infect other birds. In birds that die from WNV, death usually occurs 4–6 days.[30] In mammals, and several species of birds the virus does not multiply as readily (i.e., does not develop high viremia during infection), and mosquitoes biting infected these hosts are not believed to ingest sufficient virus to become infected, making them so-called dead-end hosts.[29] As a result of the differential infectiousness of hosts, the feeding patterns of mosquitoes play an important role in WNV transmission,[27][28] and they are partly genetically controlled, even within a species.

Direct human-to-human transmission initially was believed to be caused only by occupational exposure, such as in a laboratory setting,[31] or conjunctive exposure to infected blood.[32] The US outbreak identified additional transmission methods through blood transfusion,[33] organ transplant,[34] intrauterine exposure,[35] and breast feeding.[36] Since 2003, blood banks in the United States routinely screen for the virus among their donors.[37] As a precautionary measure, the UK's National Blood Service initially ran a test for this disease in donors who donate within 28 days of a visit to the United States, Canada, or the northeastern provinces of Italy, and the Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service[38] asks prospective donors to wait 28 days after returning from North America or the northeastern provinces of Italy before donating.

Recently, the potential for mosquito saliva to affect the course of WNV disease was demonstrated.[39][40][41] Mosquitoes inoculate their saliva into the skin while obtaining blood. Mosquito saliva is a pharmacological cocktail of secreted molecules, principally proteins, that can affect vascular constriction, blood coagulation, platelet aggregation, inflammation, and immunity. It clearly alters the immune response in a manner that may be advantageous to a virus.[42][43][44][45] Studies have shown it can specifically modulate the immune response during early virus infection,[46] and mosquito feeding can exacerbate WNV infection, leading to higher viremia and more severe forms of disease.[39][40][41]

Vertical transmission[edit]

Vertical transmission, the transmission of a viral or bacterial disease from the female of the species to her offspring, has been observed in various West Nile virus studies, amongst different species of mosquitoes in both the laboratory and in nature.[47] Mosquito progeny infected vertically in autumn, may potentially serve as a mechanism for WNV to overwinter and initiate enzootic horizontal transmission the following spring, although it likely plays little role in transmission in the summer and fall.[48]

Risk factors[edit]

Risk factors independently associated with developing a clinical infection with WNV include a suppressed immune system and a patient history of organ transplantation.[49] For neuroinvasive disease the additional risk factors include older age (>50+), male sex, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus.[50][51]

A genetic factor also appears to increase susceptibility to West Nile disease. A mutation of the gene CCR5 gives some protection against HIV but leads to more serious complications of WNV infection. Carriers of two mutated copies of CCR5 made up 4.0 to 4.5% of a sample of West Nile disease sufferers, while the incidence of the gene in the general population is only 1.0%.[52][53]

Diagnosis[edit]

An immunoglobulin M antibody molecule: Definitive diagnosis of WNV is obtained through detection of virus-specific IgM and neutralizing antibodies.

Preliminary diagnosis is often based on the patient's clinical symptoms, places and dates of travel (if patient is from a nonendemic country or area), activities, and epidemiologic history of the location where infection occurred. A recent history of mosquito bites and an acute febrile illness associated with neurologic signs and symptoms should cause clinical suspicion of WNV.

Diagnosis of West Nile virus infections is generally accomplished by serologic testing of blood serum or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which is obtained via a lumbar puncture. Typical findings of WNV infection include lymphocytic pleocytosis, elevated protein level, reference glucose and lactic acid levels, and no erythrocytes.

Definitive diagnosis of WNV is obtained through detection of virus-specific antibody IgM and neutralizing antibodies. Cases of West Nile virus meningitis and encephalitis that have been serologically confirmed produce similar degrees of CSF pleocytosis and are often associated with substantial CSF neutrophilia.[54] Specimens collected within eight days following onset of illness may not test positive for West Nile IgM, and testing should be repeated. A positive test for West Nile IgG in the absence of a positive West Nile IgM is indicative of a previous flavavirus infection and is not by itself evidence of an acute West Nile virus infection.[55]

If cases of suspected West Nile virus infection, sera should be collected on both the acute and convalescent phases of the illness. Convalescent specimens should be collected 2–3 weeks after acute specimens.

It is common in serologic testing for cross-reactions to occur among flaviviruses such as dengue virus (DENV) and tick-borne encephalitis virus; this necessitates caution when evaluating serologic results of flaviviral infections.[56]

Four FDA-cleared WNV IgM ELISA kits are commercially available from different manufacturers in the U.S., each of these kits is indicated for use on serum to aid in the presumptive laboratory diagnosis of WNV infection in patients with clinical symptoms of meningitis or encephalitis. Positive WNV test kits obtained via use of these kits should be confirmed by additional testing at a state health department laboratory or CDC.

In fatal cases, nucleic acid amplification, histopathology with immunohistochemistry, and virus culture of autopsy tissues can also be useful. Only a few state laboratories or other specialized laboratories, including those at CDC, are capable of doing this specialized testing

Differential diagnosis[edit]

A number of various diseases may present with symptoms similar to those caused by a clinical West Nile virus infection. Those causing neuroinvasive disease symptoms include the enterovirus infection and bacterial meningitis. Accounting for differential diagnoses is a crucial step in the definitive diagnosis of WNV infection. Consideration of a differential diagnosis is required when a patient presents with unexplained febrile illness, extreme headache, encephalitis or meningitis. Diagnostic and serologic laboratory testing using Polymerase chain reaction testing and viral culture of CSF to identify the specific pathogen causing the symptoms, is the only currently available means of differentiating between causes of encephalitis and meningitis.

Prevention[edit]

Personal protective measures can be taken to greatly reduce the risk of being bitten by an infected mosquito:

- Using insect repellent on exposed skin to repel mosquitoes. EPA-registered repellents include products containing DEET (N,N-diethylmetatoluamide) and picaridin (KBR 3023). DEET concentrations of 30% to 50% are effective for several hours. Picaridin, available at 7% and 15% concentrations, needs more frequent application. DEET formulations as high as 50% are recommended for both adults and children over two months of age. Protect infants less than two months of age by using a carrier draped with mosquito netting with an elastic edge for a tight fit.

- When using sunscreen, apply sunscreen first and then repellent. Repellent should be washed off at the end of the day before going to bed.

- Wear long-sleeve shirts, which should be tucked in, long pants, socks, and hats to cover exposed skin. Insect repellents should be applied over top of protective clothing for greater protection. Do not apply insect repellents underneath clothing.

- The application of permethrin-containing (e.g., Permanone) or other insect repellents to clothing, shoes, tents, mosquito nets, and other gear for greater protection. Permethrin is not labeled for use directly on skin. Most repellent is generally removed from clothing and gear by a single washing, but permethrin-treated clothing is effective for up to five washings.

- Be aware that most mosquitoes that transmit disease are most active during twilight periods (dawn and dusk or in the evening). A notable exception is the Asian tiger mosquito, which is a daytime feeder and is more apt to be found in, or on the periphery of, shaded areas with heavy vegetation. They are now widespread in the United States, and in Florida they have been found in all 67 counties.[57]

- Staying in air-conditioned or well-screened housing, and/or sleeping under an insecticide-treated bed net. Bed nets should be tucked under mattresses and can be sprayed with a repellent if not already treated with an insecticide.

Monitoring and control[edit]

West Nile virus can be sampled from the environment by the pooling of trapped mosquitoes via ovitraps, carbon dioxide-baited light traps, and gravid traps, testing blood samples drawn from wild birds, dogs, and sentinel monkeys, as well as testing brains of dead birds found by various animal control agencies and the public.

Testing of the mosquito samples requires the use of RT-PCR to directly amplify and show the presence of virus in the submitted samples. When using the blood sera of wild birds and sentinel chickens, samples must be tested for the presence of WNV antibodies by use of immunohistochemistry (IHC)[58] or Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA).[59]

Dead birds, after necropsy, or their oral swab samples collected on specific RNA-preserving filter paper card,[60][61] can have their virus presence tested by either RT-PCR or IHC, where virus shows up as brown-stained tissue because of a substrate-enzyme reaction.

West Nile control is achieved through mosquito control, by elimination of mosquito breeding sites such as abandoned pools, applying larvacide to active breeding areas, and targeting the adult population via lethal ovitraps and aerial spraying of pesticides.

Environmentalists have condemned attempts to control the transmitting mosquitoes by spraying pesticide, saying the detrimental health effects of spraying outweigh the relatively few lives that may be saved, and more environmentally friendly ways of controlling mosquitoes are available. They also question the effectiveness of insecticide spraying, as they believe mosquitoes that are resting or flying above the level of spraying will not be killed; the most common vector in the northeastern United States, Culex pipiens, is a canopy feeder.

-

A carbon dioxide-baited CDC light trap at NPSmonitoring site: The highest individual light trap total for 2010 was from a trap located in a salt marsh in the Fire Island National Seashore: around 25,142 mosquitoes were collected during a 16-hour period on August 31.[62]

-

Eggs of permanent water mosquitoes can hatch, and the larvae survive, in only a few ounces of water. Less than half the amount that may collect in a discarded coffee cup. Floodwater species lay their eggs on wet soil or other moist surfaces. Hatch time is variable for both types; under favorable circumstances, i.e. warm weather, the eggs of some species may hatch in as few as 1–3 days after being laid.[63]

-

Used tires often hold stagnant water and are a breeding ground for many species of mosquitoes. Some species such as the Asian tiger mosquito prefer manmade containers, such as tires, in which to lay their eggs. The rapid spread of this aggressive daytime feeding species beyond their native range has been attributed to the used tire trade.[57][64]

Treatment[edit]

No specific treatment is available for WNV infection. In severe cases treatment consists of supportive care that often involves hospitalization, intravenous fluids, respiratory support, and prevention of secondary infections.

Prognosis[edit]

While the general prognosis is favorable, current studies indicate that West Nile Fever can often be more severe than previously recognized, with studies of various recent outbreaks indicating that it may take as long as 60–90 days to recover.[11][65] Patients with milder WNF are just as likely as those with more severe manifestations of neuroinvasive disease to experience multiple long term (>1+ years) somatic complaints such as tremor, and dysfunction in motor skills and executive functions. Patients with milder illness are just as likely as patients with more severe illness to experience adverse outcomes.[66] Recovery is marked by a long convalescence with fatigue. One study found that neuroinvasive WNV infection was associated with an increased risk for subsequent kidney disease.[67][68]

Epidemiology[edit]

WNV was first isolated from a feverish 37-year-old woman at Omogo in the West Nile District of Uganda in 1937 during research on yellow fever virus.[69] A series of serosurveys in 1939 in central Africa found anti-WNV positive results ranging from 1.4% (Congo) to 46.4% (White Nile region, Sudan). It was subsequently identified in Egypt (1942) and India (1953), a 1950 serosurvey in Egypt found 90% of those over 40 years in age had WNV antibodies. The ecology was characterized in 1953 with studies in Egypt[70] and Israel.[71] The virus became recognized as a cause of severe human meningoencephalitis in elderly patients during an outbreak in Israel in 1957. The disease was first noted in horses in Egypt and France in the early 1960s and found to be widespread in southern Europe, southwest Asia and Australia.

The first appearance of WNV in the Western Hemisphere was in 1999[1] with encephalitis reported in humans, dogs, cats, and horses, and the subsequent spread in the United States may be an important milestone in the evolving history of this virus. The American outbreak began in College Point, Queens in New York City and was later spread to the neighboring states of New Jersey and Connecticut. The virus is believed to have entered in an infected bird or mosquito, although there is no clear evidence.[72] West Nile virus is now endemic in Africa, Europe, the Middle East, west and central Asia, Oceania (subtype Kunjin), and most recently, North America and is spreading into Central and South America.

Recent outbreaks of West Nile virus encephalitis in humans have occurred in Algeria (1994), Romania (1996 to 1997), the Czech Republic (1997), Congo (1998), Russia (1999), the United States (1999 to 2009), Canada (1999–2007), Israel (2000) and Greece (2010).

Epizootics of disease in horses occurred in Morocco (1996), Italy (1998), the United States (1999 to 2001), and France (2000), Mexico (2003) and Sardinia (2011).

Research[edit]

A vaccine for horses (ATCvet code: QI05AA10) based on killed viruses exists; some zoos have given this vaccine to their birds, although its effectiveness is unknown. Dogs and cats show few if any signs of infection. There have been no known cases of direct canine-human or feline-human transmission; although these pets can become infected, it is unlikely they are, in turn, capable of infecting native mosquitoes and thus continuing the disease cycle.[73]AMD3100, which had been proposed as an antiretroviral drug for HIV, has shown promise against West Nile encephalitis. Morpholino antisense oligos conjugated to cell penetrating peptides have been shown to partially protect mice from WNV disease.[74] There have also been attempts to treat infections using ribavirin, intravenous immunoglobulin, or alpha interferon.[75] GenoMed, a U.S. biotech company, has found that blocking angiotensin II can treat the "cytokine storm" of West Nile virus encephalitis as well as other viruses.[76]

A vaccine called Chimerivax-WNV is being actively researched and has undergone phase II Clinical trials in 2011.[77][78]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Nash D, Mostashari F, Fine A et al. (June 2001). "The outbreak of West Nile virus infection in the New York City area in 1999". N. Engl. J. Med. 344 (24): 1807–14. doi:10.1056/NEJM200106143442401. PMID 11407341. CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al. (link)

- ^ Barzon L, Pacenti M, Franchin E, Lavezzo E, Martello T, Squarzon L, Toppo S, Fiorin F, Marchiori G, Russo F, Cattai M, Cusinato R, Palu G (2012). "New endemic West Nile virus lineage 1a in northern Italy, July 2012". Euro Surveillance : Bulletin Européen Sur Les Maladies Transmissibles = European Communicable Disease Bulletin 17 (31). PMID 22874456. Retrieved 2014-12-08.

- ^ Murray KO, Ruktanonchai D, Hesalroad D, Fonken E, Nolan MS (November 2013). "West Nile virus, Texas, USA, 2012". Emerging Infectious Diseases 19 (11): 1836–8. doi:10.3201/eid1911.130768. PMC 3837649. PMID 24210089. Retrieved 2014-12-08.

- ^ Fox, M. (May 13, 2013). "2012 was deadliest year for West Nile in US, CDC says". NBC News. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ^ Steinman, A.; Banet-Noach, C.; Tal, S.; Levi, O.; Simanov, L.; Perk, S.; Malkinson, M.; Shpigel, N. (2003). "West Nile Virus Infection in Crocodiles". Emerging Infectious Diseases 9 (7): 887–889. doi:10.3201/eid0907.020816. PMC 3023443. PMID 12899140. edit

- ^ Klenk, K.; Snow, J.; Morgan, K.; Bowen, R.; Stephens, M.; Foster, F.; Gordy, P.; Beckett, S.; Komar, N.; Gubler, D.; Bunning, M. (2004). "Alligators as West Nile Virus Amplifiers". Emerging Infectious Diseases 10 (12): 2150–2155. doi:10.3201/eid1012.040264. PMC 3323409. PMID 15663852. edit

- ^ "West Nile Virus: What You Need to Know CDC Fact Sheet". www.CDC.gov. Retrieved 2012-04-09.

- ^ Olejnik E (1952). "Infectious adenitis transmitted by Culex molestus". Bull Res Counc Isr 2: 210–1.

- ^ a b Davis LE, DeBiasi R, Goade DE et al. (Sep 2006). "West Nile virus neuroinvasive disease". Ann Neurol 60 (3): 286–300. doi:10.1002/ana.20959. PMID 16983682. CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al. (link)

- ^ Flores Anticona EM, Zainah H, Ouellette DR, Johnson LE (2012). "Two case reports of neuroinvasive west nile virus infection in the critical care unit". Case Rep Infect Dis 2012: 839458. doi:10.1155/2012/839458. PMC 3433121. PMID 22966470.

- ^ a b Carson PJ, Konewko P, Wold KS et al. (2006). "Long-term clinical and neuropsychological outcomes of West Nile virus infection". Clin. Infect. Dis. 43 (6): 723–30. doi:10.1086/506939. PMID 16912946. CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al. (link)

- ^ a b c Mojumder, D. K., Agosto, M., Wilms, H. et al. (March 2014). "Is initial preservation of deep tendon reflexes in West Nile Virus paralysis a good prognostic sign?". Neurology Asia 19 (1): 93–97. CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al. (link)

- ^ Asnis DS, Conetta R, Teixeira AA, Waldman G, Sampson BA (March 2000). "The West Nile Virus outbreak of 1999 in New York: the Flushing Hospital experience". Clin. Infect. Dis. 30 (3): 413–8. doi:10.1086/313737. PMID 10722421.

- ^ Montgomery SP, Chow CC, Smith SW, Marfin AA, O'Leary DR, Campbell GL (2005). "Rhabdomyolysis in patients with west nile encephalitis and meningitis". Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 5 (3): 252–7. doi:10.1089/vbz.2005.5.252. PMID 16187894.

- ^ Smith RD, Konoplev S, DeCourten-Myers G, Brown T (February 2004). "West Nile virus encephalitis with myositis and orchitis". Hum. Pathol. 35 (2): 254–8. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2003.09.007. PMID 14991545.

- ^ Anninger WV, Lomeo MD, Dingle J, Epstein AD, Lubow M (2003). "West Nile virus-associated optic neuritis and chorioretinitis". Am. J. Ophthalmol. 136 (6): 1183–5. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(03)00738-4. PMID 14644244.

- ^ Paddock CD, Nicholson WL, Bhatnagar J et al. (June 2006). "Fatal hemorrhagic fever caused by West Nile virus in the United States". Clin. Infect. Dis. 42 (11): 1527–35. doi:10.1086/503841. PMID 16652309. CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al. (link)

- ^ Shaikh S, Trese MT (2004). "West Nile virus chorioretinitis". Br J Ophthalmol 88 (12): 1599–60. doi:10.1136/bjo.2004.049460. PMC 1772450. PMID 15548822.

- ^ Anderson RC, Horn KB, Hoang MP, Gottlieb E, Bennin B (November 2004). "Punctate exanthem of West Nile Virus infection: report of 3 cases". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 51 (5): 820–3. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.05.031. PMID 15523368.

- ^ Lanciotti RS, Ebel GD, Deubel V et al. (June 2002). "Complete genome sequences and phylogenetic analysis of West Nile virus strains isolated from the United States, Europe, and the Middle East". Virology 298 (1): 96–105. doi:10.1006/viro.2002.1449. PMID 12093177. CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al. (link)

- ^ Galli M, Bernini F, Zehender G (July 2004). "Alexander the Great and West Nile virus encephalitis". Emerging Infect. Dis. 10 (7): 1330–2; author reply 1332–3. doi:10.3201/eid1007.040396. PMID 15338540.

- ^ West, Christy (2010-02-08). "Different West Nile Virus Genetic Lineage Evolving?". The Horse, online edition. Retrieved 2010-02-10.

- ^ Venter M, Human S, van Niekerk S, Williams J, van Eeden C, Freeman F (August 2011). "Fatal neurologic disease and abortion in mare infected with lineage 1 West Nile virus, South Africa". Emerging Infect. Dis. 17 (8): 1534–6. doi:10.3201/eid1708.101794. PMC 3381566. PMID 21801644.

- ^ St Leger J, Wu G, Anderson M, Dalton L, Nilson E, Wang D (2011). "West Nile virus infection in killer whale, Texas, USA, 2007". Emerging Infect. Dis. 17 (8): 1531–3. doi:10.3201/eid1708.101979. PMC 3381582. PMID 21801643.

- ^ Hogan, C. Michael (2008). Barbary Macaque: Macaca sylvanus, GlobalTwitcher.com

- ^ Hayes EB, Komar N, Nasci RS, Montgomery SP, O'Leary DR, Campbell GL (2005). "Epidemiology and transmission dynamics of West Nile virus disease". Emerging Infect. Dis. 11 (8): 1167–73. doi:10.3201/eid1108.050289a. PMC 3320478. PMID 16102302.

- ^ a b Kilpatrick, A.M. (2011). "Globalization, land use, and the invasion of West Nile virus.". Science 334: 323–327. doi:10.1126/science.1201010. PMID 22021850.

- ^ a b c Kilpatrick, AM, P Daszak, MJ Jones, PP Marra, LD Kramer (2006). "Host heterogeneity dominates West Nile virus transmission". Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences: 2327–2333. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3575. PMID 16928635.

- ^ a b Kilpatrick, AM, SL LaDeau, PP Marra (2007). "Ecology of West Nile virus transmission and its impact on birds in the western hemisphere". Auk: 1121–1136. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2007)124[1121:eownvt]2.0.co;2.

- ^ Komar, N, S Langevin, S Hinten, N Nemeth, E Edwards, D Hettler, B Davis, R Bowen, M Bunning (2003). "Experimental infection of North American birds with the New York 1999 strain of West Nile virus". Emerging Infectious Diseases: 311–322. doi:10.3201/eid0903.020628. PMID 12643825.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2002). "Laboratory-acquired West Nile virus infections—United States, 2002". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 51 (50): 1133–5. PMID 12537288.

- ^ Fonseca K, Prince GD, Bratvold J et al. (2005). "West Nile virus infection and conjunctive exposure". Emerging Infect. Dis. 11 (10): 1648–9. doi:10.3201/eid1110.040212. PMC 3366727. PMID 16355512. CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al. (link)

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2002). "Investigation of blood transfusion recipients with West Nile virus infections". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 51 (36): 823. PMID 12269472.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2002). "West Nile virus infection in organ donor and transplant recipients—Georgia and Florida, 2002". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 51 (35): 790. PMID 12227442.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2002). "Intrauterine West Nile virus infection—New York, 2002". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 51 (50): 1135–6. PMID 12537289.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2002). "Possible West Nile virus transmission to an infant through breast-feeding—Michigan, 2002". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 51 (39): 877–8. PMID 12375687.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2003). "Detection of West Nile virus in blood donations—United States, 2003". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 52 (32): 769–72. PMID 12917583.

- ^ West Nile Virus. Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service.

- ^ a b Schneider BS, McGee CE, Jordan JM, Stevenson HL, Soong L, Higgs S (2007). Baylis, Matthew, ed. "Prior exposure to uninfected mosquitoes enhances mortality in naturally-transmitted West Nile virus infection". PLoS ONE 2 (11): e1171. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001171. PMC 2048662. PMID 18000543.

- ^ a b Styer LM, Bernard KA, Kramer LD (2006). "Enhanced early West Nile virus infection in young chickens infected by mosquito bite: effect of viral dose". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 75 (2): 337–45. PMID 16896145.

- ^ a b Schneider BS, Soong L, Girard YA, Campbell G, Mason P, Higgs S (2006). "Potentiation of West Nile encephalitis by mosquito feeding". Viral Immunol. 19 (1): 74–82. doi:10.1089/vim.2006.19.74. PMID 16553552.

- ^ Wasserman HA, Singh S, Champagne DE (2004). "Saliva of the Yellow Fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti, modulates murine lymphocyte function". Parasite Immunol. 26 (6–7): 295–306. doi:10.1111/j.0141-9838.2004.00712.x. PMID 15541033.

- ^ Limesand KH, Higgs S, Pearson LD, Beaty BJ (2003). "Effect of mosquito salivary gland treatment on vesicular stomatitis New Jersey virus replication and interferon alpha/beta expression in vitro". J. Med. Entomol. 40 (2): 199–205. doi:10.1603/0022-2585-40.2.199. PMID 12693849.

- ^ Wanasen N, Nussenzveig RH, Champagne DE, Soong L, Higgs S (2004). "Differential modulation of murine host immune response by salivary gland extracts from the mosquitoes Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus". Med. Vet. Entomol. 18 (2): 191–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2915.2004.00498.x. PMID 15189245.

- ^ Zeidner NS, Higgs S, Happ CM, Beaty BJ, Miller BR (1999). "Mosquito feeding modulates Th1 and Th2 cytokines in flavivirus susceptible mice: an effect mimicked by injection of sialokinins, but not demonstrated in flavivirus resistant mice". Parasite Immunol. 21 (1): 35–44. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3024.1999.00199.x. PMID 10081770.

- ^ Schneider BS, Soong L, Zeidner NS, Higgs S (2004). "Aedes aegypti salivary gland extracts modulate anti-viral and TH1/TH2 cytokine responses to sindbis virus infection". Viral Immunol. 17 (4): 565–73. doi:10.1089/vim.2004.17.565. PMID 15671753.

- ^ Bugbee, LM; Forte LR (September 2004). "The discovery of West Nile virus in overwintering Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) mosquitoes in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania". Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 20 (3): 326–7. PMID 15532939.

- ^ Goddard LB, Roth AE, Reisen WK, Scott TW (November 2003). "Vertical transmission of West Nile Virus by three California Culex (Diptera: Culicidae) species". J. Med. Entomol. 40 (6): 743–6. doi:10.1603/0022-2585-40.6.743. PMID 14765647.

- ^ Kumar D, Drebot MA, Wong SJ et al. (2004). "A seroprevalence study of West Nile virus infection in solid organ transplant recipients". Am. J. Transplant. 4 (11): 1883–8. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00592.x. PMID 15476490. CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al. (link)

- ^ Jean CM, Honarmand S, Louie JK, Glaser CA (December 2007). "Risk factors for West Nile virus neuroinvasive disease, California, 2005". Emerging Infect. Dis. 13 (12): 1918–20. doi:10.3201/eid1312.061265. PMC 2876738. PMID 18258047.

- ^ Kumar D, Drebot MA, Wong SJ et al. (2004). "A seroprevalence study of west nile virus infection in solid organ transplant recipients". Am. J. Transplant. 4 (11): 1883–8. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00592.x. PMID 15476490. CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al. (link)

- ^ Glass, WG; Lim JK; Cholera R; Pletnev AG; Gao JL; Murphy PM (October 17, 2005). "Chemokine receptor CCR5 promotes leukocyte trafficking to the brain and survival in West Nile virus infection". Journal of Experimental Medicine 202 (8): 1087–98. doi:10.1084/jem.20042530. PMC 2213214. PMID 16230476.

- ^ Glass, WG; McDermott DH; Lim JK; Lekhong S; Yu SF; Frank WA; Pape J; Cheshier RC; Murphy PM (January 23, 2006). "CCR5 deficiency increases risk of symptomatic West Nile virus infection". Journal of Experimental Medicine 203 (1): 35–40. doi:10.1084/jem.20051970. PMC 2118086. PMID 16418398.

- ^ Tyler KL, Pape J, Goody RJ, Corkill M, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK (February 2006). "CSF findings in 250 patients with serologically confirmed West Nile virus meningitis and encephalitis". Neurology 66 (3): 361–5. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000195890.70898.1f. PMID 16382032.

- ^ "2012 DOHMH Advisory #8: West Nile Virus" (PDF). NYC.

- ^ Papa A, Karabaxoglou D, Kansouzidou A (October 2011). "Acute West Nile virus neuroinvasive infections: cross-reactivity with dengue virus and tick-borne encephalitis virus". J. Med. Virol. 83 (10): 1861–5. doi:10.1002/jmv.22180. PMID 21837806.

- ^ a b Rios L, Maruniak JE (October 2011). "Asian Tiger Mosquito, Aedes albopictus (Skuse) (Insecta: Diptera: Culicidae)". Department of Entomology and Nematology, University of Florida. EENY-319.

- ^ Jozan, M; Evans R; McLean R; Hall R; Tangredi B; Reed L; Scott J (Fall 2003). "Detection of West Nile virus infection in birds in the United States by blocking ELISA and immunohistochemistry". Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 3 (3): 99–110. doi:10.1089/153036603768395799. PMID 14511579.

- ^ Hall, RA; Broom AK; Hartnett AC; Howard MJ; Mackenzie JS (February 1995). "Immunodominant epitopes on the NS1 protein of MVE and KUN viruses serve as targets for a blocking ELISA to detect virus-specific antibodies in sentinel animal serum". Journal of Virological Methods 51 (2–3): 201–10. doi:10.1016/0166-0934(94)00105-P. PMID 7738140.

- ^ California Department of Public Health Tutorial for Local Agencies to Safely Collect Dead Birds Oral Swab Samples on RNAse Cards for West Nile Virus Testing

- ^ RNA virus preserving filter paper card

- ^ "Mosquito Monitoring and Management". National Park Service.

- ^ Oklahoma State University: Mosquitoes and West Nile virus

- ^ Benedict MQ, Levine RS, Hawley WA, Lounibos LP (2007). "Spread of the tiger: global risk of invasion by the mosquito Aedes albopictus". Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 7 (1): 76–85. doi:10.1089/vbz.2006.0562. PMC 2212601. PMID 17417960.

- ^ Watson JT, Pertel PE, Jones RC et al. (September 2004). "Clinical characteristics and functional outcomes of West Nile Fever". Ann. Intern. Med. 141 (5): 360–5. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-141-5-200409070-00010. PMID 15353427. CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al. (link)

- ^ Klee AL, Maidin B, Edwin B et al. (Aug 2004). "Long-term prognosis for clinical West Nile virus infection". Emerg Infect Dis 10 (8): 1405–11. doi:10.3201/eid1008.030879. PMC 3320418. PMID 15496241. CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al. (link)

- ^ Nolan MS, Podoll AS, Hause AM, Akers KM, Finkel KW, Murray KO (2012). Wang, Tian, ed. "Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and progression of disease over time among patients enrolled in the Houston West Nile virus cohort". PLoS ONE 7 (7): e40374. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040374. PMC 3391259. PMID 22792293.

- ^ "New Study Reveals: West Nile virus is far more menacing & harms far more people". The Guardian Express. The Guardian Express. 26 August 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ Smithburn KC, Hughes TP, Burke AW, Paul JH (June 1940). "A Neurotropic Virus Isolated from the Blood of a Native of Uganda". Am. J. Trop. Med. 20 (1): 471–92.

- ^ Work TH, Hurlbut HS, Taylor RM (1953). "Isolation of West Nile virus from hooded crow and rock pigeon in the Nile delta". Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 84 (3): 719–22. doi:10.3181/00379727-84-20764. PMID 13134268.

- ^ Bernkopf H, Levine S, Nerson R (1953). "Isolation of West Nile virus in Israel". J. Infect. Dis. 93 (3): 207–18. doi:10.1093/infdis/93.3.207. PMID 13109233.

- ^ Calisher CH (2000). "West Nile virus in the New World: appearance, persistence, and adaptation to a new econiche—an opportunity taken". Viral Immunol. 13 (4): 411–4. doi:10.1089/vim.2000.13.411. PMID 11192287.

- ^ "Vertebrate Ecology". West Nile Virus. Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, CDC. 30 April 2009.

- ^ Deas, Tia S; Bennett CJ, Jones SA, Tilgner M, Ren P, Behr MJ, Stein DA, Iversen PL, Kramer LD, Bernard KA, Shi PY (May 2007). "In vitro resistance selection and in vivo efficacy of morpholino oligomers against West Nile virus". Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51 (7): 2470–82. doi:10.1128/AAC.00069-07. PMC 1913242. PMID 17485503. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ^ Hayes EB, Sejvar JJ, Zaki SR, Lanciotti RS, Bode AV, Campbell GL (2005). "Virology, pathology, and clinical manifestations of West Nile virus disease". Emerging Infect. Dis. 11 (8): 1174–9. doi:10.3201/eid1108.050289b. PMC 3320472. PMID 16102303.

- ^ Moskowitz DW, Johnson FE (2004). "The central role of angiotensin I-converting enzyme in vertebrate pathophysiology". Curr Top Med Chem 4 (13): 1433–54. doi:10.2174/1568026043387818. PMID 15379656.

- ^ Arroyo, J.; Miller, C.; Catalan, J.; Myers, G. A.; Ratterree, M. S.; Trent, D. W.; Monath, T. P. (2004). "ChimeriVax-West Nile Virus Live-Attenuated Vaccine: Preclinical Evaluation of Safety, Immunogenicity, and Efficacy". Journal of Virology 78 (22): 12497–12507. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.22.12497-12507.2004. PMC 525070. PMID 15507637.

- ^ Biedenbender, R.; Bevilacqua, J.; Gregg, A. M.; Watson, M.; Dayan, G. (2011). "Phase II, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Multicenter Study to Investigate the Immunogenicity and Safety of a West Nile Virus Vaccine in Healthy Adults". Journal of Infectious Diseases 203 (1): 75–84. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiq003. PMC 3086439. PMID 21148499.

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Wikipedia |

| Source | http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=West_Nile_virus&oldid=654344825 |

Kunjin virus (KUNV) is a zoonotic virus of the family Flaviviridae and the genus Flavivirus. It is a subtype of West Nile Virus endemic to Oceania.

Contents

History[edit]

The virus was first isolated from Culex annulirostris mosquitoes in Australia in 1960.[1][2] The name of Kunjin virus derives from an Aboriginal clan living on the Mitchell River close to where the virus was first isolated in Kowanyama, northern Queensland.[1][3]

Virology[edit]

Kunjin virus is a zoonotic virus of the family Flaviviridae and the genus Flavivirus. It is an arbovirus which is transmitted by mosquitoes and is part of the Japanese encephalitis serological complex.[4] It is antigenically and genetically very similar to West Nile virus and in 1999 was reclassified as a subtype of WNV.[3][5] Its genome is positive-sense single stranded RNA made up of 10,644 nucleotides.[3][4]

Symptoms and prognosis[edit]

Infection with the virus often causes no symptoms, but it can lead to either an encephalitic disease or a non-encephalitic disease.[6] Non-encephalitic Kunjin virus disease can cause symptoms including acute febrile illness, headache, arthralgia, myalgia, fatigue and rash.[1][6] Kunjin virus encephalitis features acute febrile meningoencephalitis.[1]

Both forms of Kunjin virus disease are milder than the diseases caused by West Nile virus and Murray Valley encephalitis virus.[5][6]

Transmission and control[edit]

Kunjin virus is transmitted by mosquito vectors, especially the Culex annulirostris.[3] They pass the virus to waterbird reservoir hosts; a major example is the nankeen night heron.[3] It is also passed to horses and humans.[7] The virus been isolated in mosquitoes in South East Asia but in humans, only in Australia.[6] It has been found all over Australia and is particularly prevalent in areas near wetlands and rivers.[8]

The control of Kunjin virus is achieved in the same ways as other mosquito-borne diseases. These include individuals using insect repellent, wearing long-sleeved clothes and avoiding areas where mosquitoes are particularly prevalent.[1] Habitat control by government agencies can take the form of reducing the amount of water available for mosquitoes to breed in, and the use of insecticides.[9] There is no available vaccine against Kunjin virus.[1]

Use in medicine[edit]

In 2005, scientists at the Queensland Institute of Medical Research and the University of Queensland found that modified Kunjin virus particles injected into mice were able to deliver a gene into the immune system targeting cancer cells.[10][11] This research may lead to vaccines for cancer and HIV.[10][11]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f "Department of Health and Ageing — Kunjin virus infection — Fact Sheet". Government of Australia. 2004-05-25. Retrieved 2009-08-08. [dead link]

- ^ Krauss, H. (2003). Zoonoses. ASM Press. p. 45. ISBN 1-55581-236-8.

- ^ a b c d e Mackenzie, John S.; R. W. Ashford; M. W. Service (2001). Encyclopedia of arthropod-transmitted infections of man and domesticated animals. CABI. p. 251. ISBN 0-85199-473-3.

- ^ a b Hirsh, Dwight C.; Nigel James Maclachlan; Richard L. Walker (2004). Veterinary microbiology. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 354. ISBN 0-8138-0379-9.

- ^ a b Bhattacharya, Shaoni (2003-08-12). "West Nile Virus's milder cousin gives vaccine hope". New Scientist. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ a b c d Cook, Gordon C.; Alimuddin I. Zumla (2008). Manson's tropical diseases. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 736–7. ISBN 1-4160-4470-1.

- ^ Scherret, Jacqueline H.; Michael Poidinger (Jul–Aug 2001). "The Relationships between West Nile and Kunjin Viruses". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ Adlam, Nigel (2008-03-20). "Heavy rains bring mozzie diseases". Northern Territory News. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ Russell, Richard C.; Stephen L. Doggett. "Murray Valley Encephalitis virus & Kunjin virus". University of Sydney — Department of Medical Entomology. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ a b "Australian virus may lead to cancer vaccine". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2005-03-31. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ a b "New medical uses for the Kunjin virus". News-Medical.Net. 2005-04-12. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Wikipedia |

| Source | http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Kunjin_virus&oldid=654411262 |