You are here

Species

Cyprinidae

IUCN

NCBI

EOL Text

Carp are various species of oily[1]freshwater fish of the family Cyprinidae, a very large group of fish native to Europe and Asia. The cypriniformes (family Cyprinidae) are traditionally grouped with the Characiformes, Siluriformes and Gymnotiformes to create the superorder Ostariophysi, since these groups have certain common features, such as being found predominantly in fresh water and that they possess Weberian ossicles (an anatomical structure originally made up of small pieces of bone formed from four or five of the first vertebrae); the most anterior bony pair is in contact with the extension of the labyrinth and the posterior with the swimbladder. The function is poorly understood, but this structure is presumed to take part in the transmission of vibrations from the swimbladder to the labyrinth and in the perception of sound, which would explain why the Ostariophysi have such a great capacity for hearing.[2]

Most cypriniformes have scales and teeth on the inferior pharyngeal bones which may be modified in relation to the diet. Tribolodon is the only cyprinid genus which tolerates salt water, although there are several species which move into brackish water, but return to fresh water to spawn. All of the other cypriniformes live in continental waters and have a wide geographical range.[2]

Some consider all cyprinid fishes carp, and the family Cyprinidae itself is often known as the carp family. In colloquial use, however, carp usually refers only to several larger cyprinid species such as Cyprinus carpio (common carp), Carassius carassius (Crucian carp), Ctenopharyngodon idella (grass carp), Hypophthalmichthys molitrix (silver carp), and Hypophthalmichthys nobilis (bighead carp). Carp have long been an important food fish to humans, as well as popular ornamental fishes such as the various goldfish breeds and the domesticated common carp variety known as koi. As a result, carp have been introduced to various locations, though with mixed results. Several species of carp are listed as invasive species by the U.S. Department of Agriculture,[3] and worldwide large sums of money are spent on carp control.

Contents |

Species

| This article is one of a series on |

| Commercial fish |

|---|

| Large pelagic |

| billfish, bonito mackerel, salmon shark, tuna |

|

|

| Forage |

| anchovy, herring menhaden, sardine shad, sprat |

|

|

| Demersal |

| cod, eel, flatfish pollock, ray |

| Mixed |

| carp |

| Some prominent carp in the family Cyprinidae | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common name | Scientific name | Maximum length |

Common length |

Maximum weight |

Maximum age |

Trophic level |

Fish Base |

FAO | ITIS | IUCN status |

| Silver carp | Hypophthalmichthys molitrix (Valenciennes, 1844) | 105 cm | 18 cm | 50 kg | years | 2.0 | [4] | [5] | [6] | |

| Common carp | Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus, 1758 | 110 cm | 31 cm | 40.1 kg | 38 years | 3.0 | [8] | [9] | [10] | |

| Grass carp | Ctenopharyngodon idella (Valenciennes, 1844) | 150 cm | 10.7 cm | 45.0 kg | 21 years | 2.0 | [12] | [13] | Not assessed | |

| Bighead carp | Hypophthalmichthys nobilis (Richardson, 1845) | 146 cm | 60 cm | 40.0 kg | 20 years | 2.3 | [14] | [15] | Not assessed | |

| Crucian carp | Carassius carassius (Linnaeus, 1758) | 64 cm | 15 cm | 3.0 kg | 10 years | 3.1 | [16] | [17] | ||

| Catla carp (Indian carp) | Cyprinus catla (Hamilton, 1822) | 182 cm | cm | 38.6 kg | years | 2.8 | [19] | [20] | Not assessed | |

| Mrigal carp (Indian/white carp) | Cirrhinus cirrhosus (Bloch, 1795) | 100 cm | 40 cm | 12.7 kg | years | 2.5 | [21] | [22] | ||

| Black carp | Mylopharyngodon piceus (Richardson, 1846) | 122 cm | 12.2 cm | 35 kg | 13 years | 3.2 | [24] | [25] | Not assessed | |

| Mud Carp | Cirrhinus molitorella (Valenciennes, 1844) | 55.0 cm | 15.2 cm | 0.50 kg | years | 2.0 | [26] | [27] | ||

Characteristics

Life cycle

Distribution

Ecology

Recreational fishing

Izaak Walton said about carp in The Compleat Angler, "The Carp is the queen of rivers; a stately, a good, and a very subtle fish; that was not at first bred, nor hath been long in England, but is now naturalised."

Carp are variable in terms of angling value.

- In Europe, even when not fished for food, they are eagerly sought by anglers, being considered highly prized coarse fish that are difficult to hook.[29] The UK has a thriving carp angling market. It is the fastest growing angling market in the UK, and has spawned a number of specialised carp angling publications such as 'Carpology',[30] 'advanced carp fishing', 'carpworld', 'TotalCarp' and karper, and many informative carp angling web sites, such as Carpfishing UK [31] and Carpit[32] Carp Anglers Bulgaria[33]

- In the United States, carp are also classified as a rough fish, as well as damaging to naturalized exotic species, but with sporting qualities. Many states' departments of natural resources are beginning to view the carp as an angling fish instead of a maligned pest. Groups such as the Carp Anglers Group[34] and American Carp Society[35] promote the sport and work with fisheries departments to organize events to introduce and expose others to the unique opportunity the carp offers freshwater anglers.

Aquaculture

Various species of carp have been domesticated and reared as food fish across Europe and Asia for thousands of years. These various species appear to have been domesticated independently, as the various domesticated carp species are native to different parts of Eurasia. Aquaculture has been pursued in China for at least 2,400 years. A tract by Fan Li in the fifth century BC details many of the ways carp were raised in ponds.[36] The common carp, Cyprinus carpio, is originally from Central Europe.[37] Several carp species (collectively known as Asian carp) were domesticated in East Asia. Carp that are originally from South Asia, for example catla (Gibelion catla), rohu (Labeo rohita) and mrigal (Cirrhinus cirrhosus), are known as Indian carp. Their hardiness and adaptability have allowed domesticated species to be propagated all around the world.

Although the carp was an important aquatic food item, as more fish species have become readily available for the table, the importance of carp culture in Western Europe has become less important. Demand has declined, partly due to the appearance of more desirable table fish such as trout and salmon through intensive farming, and environmental constraints. However, fish production in ponds is still a major form of aquaculture in Central and Eastern Europe, including the Russian Federation, where most of the production comes from low or intermediate-intensity ponds. In Asia, the farming of carp continues to surpass the total amount of farmed fish volume of intensively sea-farmed species, such as salmon and tuna.[38]

| The major traditional aquaculture carp of China | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

Breeding

Selective breeding programs for the Common carp (Cyprinus carpio) include improvement in growth, shape and resistance to disease. Experiments carried out in the USSR used crossings of broodstocks to increase genetic diversity and then selected the species for traits like growth rate, exterior traits and viability, and/or adaptation to environmental conditions like variations in temperature.[39][40] selected carp for fast growth and tolerance to cold, the Ropsha carp. The results showed a 30-40% to 77.4% improvement of cold tolerance but did not provide any data for growth rate. An increase in growth rate was observed in the second generation in Vietnam ,[41] Moav and Wohlfarth (1976) showed positive results when selecting for slower growth for three generations compared to selecting for faster growth.[42] Schaperclaus (1962) showed resistance to the dropsy disease wherein selected lines suffered low mortality (11.5%) compared to unselected (57%).[43]

The major carp species used traditionally in Chinese aquaculture are the black, grass, silver and bighead carp. In the 1950s, the Pearl River Fishery Research Institute in China made a technological breakthrough in the induced breeding of these carps, which has resulted in a rapid expansion of freshwater aquaculture in China.[44] In the late 1990s, scientists at the Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences developed a new variant of the common carp called the Jian carp. This succulent fish grows rapidly and has a high feed conversion rate. Over 50% of the total aquaculture production of carp in China has now converted to Jian carp.[45][44]

As food

- Bighead carp is enjoyed in many parts of the world, but it has not become a popular foodfish in North America. Acceptance there has been hindered in part by the name "carp", and its association with the common carp which is not a generally favored foodfish in North America. The flesh of the bighead carp is white and firm, different to that of the common carp, which is darker and richer. Bighead carp flesh does share one unfortunate similarity with common carp flesh - both have intramuscular bones within the filet. However, bighead carp captured from the wild in the United States tend to be much larger than common carp, so the intramuscular bones are also larger and less problematic. The Louisiana State University Agricultural Research and Extension Center has a series of videos showing how to prepare the fish and deal with these bones.

- Crucian carp is considered the best-tasting pan fish in Poland. It is known as (Polish: karaś), and is served traditionally with sour cream (karasie w śmietanie).[46] In Russia, this particular species is called Russian: Золотой карась meaning "golden crucian", and is one of the fish used in a borscht recipe called borshch c karasej[47] (Russian: Борщ с карасе́й)or borshch c karasyami Russian: Борщ с карася́ми).

- Mud carp – due to the low cost of production, the fish is mainly consumed by the poor and locally consumed; it is mostly sold and eaten live, but can be dried and salted.[48] The fish is sometimes canned or processed as fish cakes, fish balls [49] or dumplings. They can be found for retail sale within China.[50]

-

- Chinese mud carp is an important food fish in Guangdong Province. It is also cultured in this area and Taiwan. Cantonese and Shunde cuisines often use this fish to make fish balls and dumplings. It can be used with douchi or Chinese fermented black beans in a dish called fried dace with salted black beans. It can be served cooked with vegetables such as Chinese cabbage.

-

Carp fish in spices and herbs cooked in a banana leaf package, Sundanese

-

Deep fried chunk of pickled (Pla som) Silver Barb (Pla taphian)

As ornamental fish

Carp, along with many of their cyprinid relatives, are popular ornamental aquarium and pond fish. The two most notable ornamental carps are goldfish and koi. Goldfish and koi have advantages over most other ornamental fishes, in that they are tolerant of cold (they can survive in water temperatures as low as 4°C), can survive at low oxygen levels, and can tolerate low water quality.[citation needed]

Goldfish (Carassius auratus) were originally domesticated from the Prussian carp (Carassius gibelio), a dark greyish-brown carp native to Asia. They were first bred for color in China over a thousand years ago. Due to selective breeding, goldfish have been developed into many distinct breeds, and are found in various colors, color patterns, forms and sizes far different from those of the original carp. Goldfish were kept as ornamental fish in Japan for hundreds of years before being introduced to China in the 15th century, and to Europe in the late 17th century.[citation needed]

Koi are a domesticated variety of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) that have been selectively bred for color. The common carp was introduced from China to Japan, where selective breeding of the common carp in the 1820s in the Niigata region resulted in koi.[51] In Japanese culture, koi are treated with affection, and seen as good luck. They are popular in other parts of the world as outdoor pond fish.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Cyprinus carpio |

References

- ^ "What's an oily fish?". Food Standards Agency. 2004-06-24. http://www.food.gov.uk/news/newsarchive/2004/jun/oilyfishdefinition.

- ^ a b Billard R. (Ed.) (1995). Carp – Biology and Culture. Springer-Praxis Series in Aquaculture and Fisheries, Chichester, UK.

- ^ National Invasive Species Information Center (2010-07-21). "Invasive Species: Aquatic Species - Asian Carp". Invasivespeciesinfo.gov. http://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/aquatics/asiancarp.shtml. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ^ Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2012). "Hypophthalmichthys molitrix" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ^ Hypophthalmichthys molitrix (Valenciennes, 1844) FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved May 2012.

- ^ "Hypophthalmichthys molitrix". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=163691. Retrieved May 2012.

- ^ Zhao H (2011). "Hypophthalmichthys molitrix". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/166081. Retrieved May 2012.

- ^ Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2012). "Cyprinus carpio" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ^ Cyprinus carpio (Linnaeus, 1758) FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved May 2012.

- ^ "Cyprinus carpio". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=163344. Retrieved May 2012.

- ^ Freyhof J and Kottelat M (2008). "Cyprinus carpio". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/6181/0. Retrieved May 2012.

- ^ Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2012). "Ctenopharyngodon idella" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ^ "Ctenopharyngodon idella". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=163537. Retrieved May 2012.

- ^ Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2012). "Hypophthalmichthys nobilis" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ^ "Hypophthalmichthys nobilis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=163692. Retrieved May 2012.

- ^ Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2012). "Carassius carassius" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ^ "Carassius carassius". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=163352. Retrieved May 2012.

- ^ Freyhof J and Kottelat M (2008). "Carassius carassius". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/3849/0. Retrieved May 2012.

- ^ Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2012). "Cyprinus catla" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ^ "Cyprinus catla". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=vvvvvvvvvvvv. Retrieved May 2012.

- ^ Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2012). "Cirrhinus cirrhosus" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ^ "Cirrhinus cirrhosus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=688892. Retrieved May 2012.

- ^ Rema Devi KR and Ali A (2011). "Cirrhinus cirrhosus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/166531/0. Retrieved May 2012.

- ^ Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2012). "Mylopharyngodon piceus" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ^ "Mylopharyngodon piceus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=639618. Retrieved May 2012.

- ^ Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2012). "Cirrhinus molitorella" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ^ "Cirrhinus molitorella". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=688897. Retrieved May 2012.

- ^ Sobel J (2009). "Cirrhinus molitorella". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/166016/0. Retrieved May 2012.

- ^ A. F. Magri MacMahon (1946). Fishlore, pp 149-152. Pelican Books.

- ^ Carpology

- ^ Carpfishing UK

- ^ Carpit and

- ^ Carp Anglers Bulgaria

- ^ Carp Anglers Group

- ^ American Carp Society

- ^ National Aquaculture Sector Overview: China FAO, Rome. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ^ SpringerLink - Journal Article, www.springerlink.com

- ^ Váradi, L. (2001). Review of trends in the development of European inland aquaculture linkages with fisheries. Fisheries Management and Ecology, 8: 453-462.

- ^ Kirpichnikov, V.S., IIYAsov, J.I., Shart, L.A., Vikhman, A.A., Ganchenko, M.V., Ostashevsky, A.L., Simonov, V.M., Tikhonov, G.F & Tjurin, V.V. 1993. Selection of Krasnodar common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) for resistance to dropsy: principal results and prospects. Aquaculture, 111:7–20.

- ^ Babouchkine, Y.P., 1987. La sélection d’une carpe résistant à l’hiver. In: Tiews, K. (Ed.), Proceedings ofWorld Symposium on Selection,Hybridization, and Genetic Engineering in Aquaculture, Bordeaux 27–30 May 1986, vol. 1. HeenemannVerlagsgesellschaft mbH, Berlin, pp. 447–454.

- ^ Tran, M.T., Nguyen, C.T. 1993. Selection of common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) in Vietnam. Aquaculture 111: 301–302.

- ^ Moav, R.,Wohlfarth, G.W., 1976. Two way selection for growth rate in the common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). Genetics 82, 83–101.

- ^ Schäperclaus,W. 1962. Traité de pisciculture en étang. Vigot Frères, Paris

- ^ a b CAFS research achievement CAFS. Accessed 26 July 2011.

- ^ Jian, Zhu; Jianxin, Wang; Yongsheng, Gong and Jiaxin, Chen (2005) "Carp Genetic Resources of China" pp. 26–38. In: David J Penman, Modadugu V Gupta and Madan M Dey (Eds.) Carp genetic resources for aquaculture in Asia, WorldFish Center, Technical report: 65(1727). ISBN 978-983-2346-35-7.

- ^ Strybel & Strybel 2005,p.384

- ^ Molokhovet︠s︡ 1998

- ^ http://www.thefishsite.com/articles/809/cultured-aquatic-species-mud-carp

- ^ http://www.clovegarden.com/ingred/sf_carpz.html

- ^ http://www.thefishsite.com/articles/809/cultured-aquatic-species-mud-carp

- ^ "Midwest Pond and Koi Society - Koi History: Myths & Mysteries, by Ray Jordan". Mpks.org. http://www.mpks.org/articles/RayJordan/KoiHistory3.shtml. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Wikipedia |

| Source | http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Carp&oldid=494270951 |

The family Cyprinidae, carps and minnows, contains about eight percent of the world’s fish. The largest of the freshwater fish families, and the second largest vertebrate family (with Gobiidae – the gobies – the largest), Cyprinidae has over 2400 species in 220 genera (Nelson, 2006). Cyprinids are native to North America, Eurasia and Africa; fossil evidence suggests that this family may have originated in Asia in the Eocene. There are several characteristics of cyprinid fish:

• Their jaws are toothless; they chew their food using one or two rows of pharyngeal teeth and with gill rakers.

• They usually have large scales, but these are almost always absent from their head. They often have barbels around their mouth, and have no adipose fin. Cyprinids range in size from the 12 mm Danionella tanslucida to the 2.5 M long Catlocarpio siamensis

• Cyprinids are egg-layers that mostly spawn their eggs with no parental care.

• As members of the superorder Ostareophysi, cyprinids have a Weberian organ. This is a set of boney ossicles that connect the inner ear to the swim bladder, thus amplifying sound waves and allowing fishes to perceive a far greater range of auditory stimuli. This apparatus is thought to be important in the enormous diversification of otophysan fishes.

Many cypridid species are important food fish for humans, some have been farmed and fished for centuries. Popular sport fish, cyprinids are frequently stocked in ponds. Some are used as biocontrol agents to remove pests such as mosquitos, many are popular in the aquarium trade and as ornamental pets, and Danio rerio is an important organism bred in laboratories to study genetics and development. Cyprinids have been introduced world-wide and some cyprinids have become highly invasive. Cyprinus carpio, the common carp, is on the Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG)’s list of the world’s 100 worst invasive alien species.

(Rainer and Pauly 2010; ISSG; Nelson 2006; Wikipedia 2012)

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Dana Campbell, Dana Campbell |

| Source | No source database. |

Cyprinidae (minnow) is prey of:

Butorides virescens

Megaceryle alcyon

Salvelinus

Lota

Actinopterygii

Vertebrata

Esocidae

Based on studies in:

USA: New York, Long Island (Marine)

USA: Maine (Lake or pond)

USA: Texas (Lake or pond)

England, River Cam (River)

This list may not be complete but is based on published studies.

- G. M. Woodwell, Toxic substances and ecological cycles, Sci. Am. 216(3):24-31, from pp. 26-27 (March 1967).

- J. L. Brooks and E. S. Deevey, New England. In: Limnology in North America, D. G. Frey, Ed. (Univ. of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 1963), pp. 117-162, from p. 143.

- B. C. Patten and 40 co-authors, Total ecosystem model for a cove in Lake Texoma. In: Systems Analysis and Simulation in Ecology, B. C. Patten, Ed. (Academic Press, New York, 1975), 3:205-421, from pp. 236, 258, 268.

- P. H. T. Hartley, Food and feeding relationships in a community of fresh-water fishes, J. Anim. Ecol. 17(1):1-14, from p. 12 (1948).

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Cynthia Sims Parr, Joel Sachs, SPIRE |

| Source | http://spire.umbc.edu/fwc/ |

Cyprinidae (minnow) preys on:

Plantae

plankton

Squamata

phytoplankton

algae

zooplankton

suspension-feeding invertebrates

Actinopterygii

invertebrates

Simulium

Baetis

Based on studies in:

USA: New York, Long Island (Marine)

USA: Texas (Lake or pond)

USA: Maine (Lake or pond)

England, River Cam (River)

This list may not be complete but is based on published studies.

- G. M. Woodwell, Toxic substances and ecological cycles, Sci. Am. 216(3):24-31, from pp. 26-27 (March 1967).

- J. L. Brooks and E. S. Deevey, New England. In: Limnology in North America, D. G. Frey, Ed. (Univ. of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 1963), pp. 117-162, from p. 143.

- B. C. Patten and 40 co-authors, Total ecosystem model for a cove in Lake Texoma. In: Systems Analysis and Simulation in Ecology, B. C. Patten, Ed. (Academic Press, New York, 1975), 3:205-421, from pp. 236, 258, 268.

- P. H. T. Hartley, Food and feeding relationships in a community of fresh-water fishes, J. Anim. Ecol. 17(1):1-14, from p. 12 (1948).

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Cynthia Sims Parr, Joel Sachs, SPIRE |

| Source | http://spire.umbc.edu/fwc/ |

Barcode of Life Data Systems (BOLD) Stats

Specimen Records:18292

Specimens with Sequences:17125

Specimens with Barcodes:15592

Species:1606

Species With Barcodes:1538

Public Records:9311

Public Species:1268

Public BINs:1214

|

|

This article has an unclear citation style. The references used may be made clearer with a different or consistent style of citation, footnoting, or external linking. (January 2011) |

Cyprinidae is a large family of freshwater fishes, including the carps, the true minnows, and their relatives (for example, the barbs and barbels). Commonly called the carp family or the minnow family, its members are also known as cyprinids. It is the largest fish family and the largest family of vertebrate animals in general, with over 2,400 species in about 220 genera. The family belongs to the order Cypriniformes, of whose genera and species the cyprinids make up two-thirds.[1] The family name is derived from the Ancient Greek kyprînos (κυπρῖνος, "carp").

Cyprinids are stomachless fish with toothless jaws. Even so, food can be effectively chewed by the gill rakers of the specialized last gill bow. These pharyngeal teeth allow the fish to make chewing motions against a chewing plate formed by a bony process of the skull. The pharyngeal teeth are species-specific and are used by specialists to determine species. Strong pharyngeal teeth allow fish such as the common carp and ide to eat hard baits like snails and bivalves.

Hearing is a well-developed sense, since the cyprinids have the Weberian organ, three specialized vertebral processes that transfer motion of the gas bladder to the inner ear. This construction is also used to observe motion of the gas bladder due to atmospheric conditions or depth changes. The cyprinids are physostomes because the pneumatic duct is retained in adult stages and the fish are able to gulp air to fill the gas bladder or they can dispose excess gas to the gut.

The fish in this family are native to North America, Africa, and Eurasia. The largest member of this family is the giant barb (Catlocarpio siamensis), which may grow up to 3 m (9.8 ft) in length and 300 kg (660 lb) in weight.[2] The largest North American species is the Colorado pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus lucius), of which individuals up to 1.8 m (5.9 ft) long[3] and weighing over 45 kg (100 lb) have been recorded.[citation needed] Conversely, many species are smaller than 5 cm (2 in). The smallest known fish is Paedocypris progenetica, reaching 10.3 mm (0.41 in) at the longest.[4]

All fish in this family are egg-layers and most do not guard their eggs; however, a few species build nests and/or guard the eggs. The bitterling-like cyprinids (Acheilognathinae) are notable for depositing their eggs in bivalve molluscs, where the young grow until able to fend for themselves.

Most cyprinids feed mainly on invertebrates and vegetation, probably due to the lack of teeth and stomach, but some species, like the asp, specialize in fish. Many species (ide, common rudd) will eat small fish when they reach a certain size. Even small species, such as the moderlieschen, eat larvae of the common frog in artificial circumstances.

Some fish, such as the grass carp, are specialized in eating vegetation; others, such as the common nase, eat algae from hard surfaces, while others, such as the black carp, specialize in snails, and some, such as the silver carp, are specialized filter feeders. For this reason, they are often introduced as a management tool to control various factors in the aquatic environment, such as aquatic vegetation and diseases transmitted by snails.

Contents

Relationship with humans[edit]

Cyprinids are highly important food fish; they are fished and farmed across Eurasia. In land-locked countries in particular, cyprinids are often the major species of fish eaten because they make the largest part of biomass in most water types except for fast-flowing rivers. In Eastern Europe, they are often prepared with traditional methods, such as drying and salting. The prevalence of inexpensive frozen fish products made this less important now than it was in earlier times. Nonetheless, in certain places, they remain popular for food, as well as recreational fishing, and have been deliberately stocked in ponds and lakes for centuries for this reason.[6]

Cyprinids are popular for angling especially for match fishing (due to their dominance in biomass and numbers) and fishing for common carp because of its size and strength.

Several cyprinids have been introduced to waters outside their natural ranges to provide food, sport, or biological control for some pest species. The common carp (Cyprinus carpio) and the grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) are the most important of these, for example in Florida. In some cases, such as the asian carp in the Mississippi Basin, they have become invasive species that compete with native fishes or disrupt the environment. Carp in particular can stir up sediment, reducing the clarity of the water and making it difficult for plants to grow.[7]

Numerous cyprinids have become important in the aquarium hobby, most famously the goldfish, which was bred in China from the Prussian carp (Carassius (auratus) gibelio). First imported into Europe around 1728, it was much fancied by Chinese nobility as early as 1150 AD and after it arrived there in 1502, also in Japan. In the latter country, from the 18th century onwards, the common carp was bred into the ornamental variety known as koi – or more accurately nishikigoi (錦鯉), as koi (鯉) simply means "common carp" in Japanese.

Other popular aquarium cyprinids include danionins, rasborines, and true barbs.[8] Larger species are bred by the thousands in outdoor ponds, particularly in Southeast Asia, and trade in these aquarium fishes is of considerable commercial importance. The small rasborines and danionines are perhaps only rivalled by characids and poecilid livebearers in their popularity for community aquaria.[citation needed]

One particular species of these small and undemanding danionines is the zebrafish (Danio rerio). It has become the standard model species for studying developmental genetics of vertebrates, in particular fish.[9]

Habitat destruction and other causes have reduced the wild stocks of several cyprinids to dangerously low levels; some are already entirely extinct. In particular, the Leuciscinae from southwestern North America have been hit hard by pollution and unsustainable water use in the early to mid-20th century; most globally extinct Cypriniformes species are in fact Leuciscinae from the southwestern United States and northern Mexico.

Systematics[edit]

The massive diversity of cyprinids has so far made it difficult to resolve their phylogeny in sufficient detail to make assignment to subfamilies more than tentative in many cases. Some distinct lineages obviously exist – for example, Cultrinae and Leuciscinae, regardless of their exact delimitation, are rather close relatives and stand apart from Cyprininae –, but the overall systematics and taxonomy of the Cyprinidae remain a subject of considerable debate. A large number of genera are incertae sedis, too equivocal in their traits and/or too little-studied to permit assignment to a particular subfamily with any certainty.[10]

Part of the solution seems that the delicate rasborines are the core group, consisting of minor lineages that have not shifted far from their evolutionary niche, or have coevolved for millions of years. These are among the most basal lineages of living cyprinids. Other "rasborines" are apparently distributed across the diverse lineages of the family.[11]

The validity and circumscription of proposed subfamilies like Labeoninae or Squaliobarbinae also remains doubtful, although the latter do appear to correspond to a distinct lineage. The sometimes-seen grouping of the large-headed carps (Hypophthalmichthyinae) with Xenocypris, though, seems quite in error. More likely, the latter are part of the Cultrinae.[11]

The entirely paraphyletic "Barbinae" and the disputed Labeoninae might be better treated as part of the Cyprininae, forming a close-knit group whose internal relationships are still little known. The small African "barbs" do not belong in Barbus sensu stricto – indeed, they are as distant from the typical barbels and the typical carps (Cyprinus) as these are from Garra (which is placed in the Labeoninae by most who accept the latter as distinct) and thus might form another as yet unnamed subfamily. However, as noted above, how various minor lineages tie into this has not yet been resolved; therefore, such a radical move, though reasonable, is probably premature.[12]

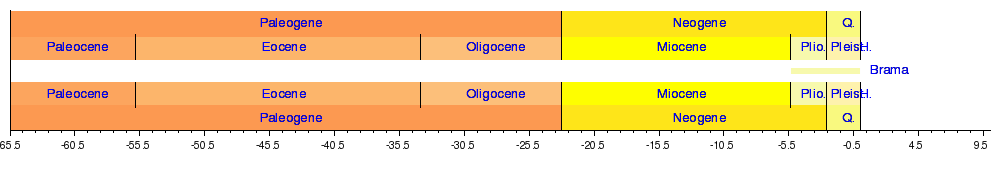

The tench (Tinca tinca), a significant food species farmed in western Eurasia in large numbers, is unusual. It is most often grouped with the Leuciscinae, but even when these were rather loosely circumscribed, it always stood apart. A cladistic analysis of DNA sequence data of the S7 ribosomal protein intron 1 supports the view that it is distinct enough to constitute a monotypic subfamily. It also suggests it may be closer to the small East Asian Aphyocypris, Hemigrammocypris, and Yaoshanicus. They would have diverged roughly at the same time from cyprinids of east-central Asia, perhaps as a result of the Alpide orogeny that vastly changed the topography of that region in the late Paleogene, when their divergence presumably occurred.[13]

A DNA-based analysis of these fish places Rasborinae as the basal lineage with Cyprininae as a sister clade to Leuciscinae.[14] The subfamilies Acheilognathinae, Gobioninae, and Leuciscinae are monophylitic.

Subfamilies and genera[edit]

Subfamily Leuciscinae

|

|

|

Subfamily Rasborinae (rasborines)

Subfamily Squaliobarbinae

|

Subfamily Tincinae

Subfamily Xenocyprinae

|

Unlike most fish species, cyprinids generally increase in abundance in eutrophic lakes. Here, they contribute towards positive feedback as they are efficient at eating the zooplankton that would otherwise graze on the algae, reducing its abundance.

Timeline[edit]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ FishBase (2004), Nelson (2006), dictionary.com [2009]

- ^ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2015). "Catlocarpio siamensis" in FishBase. March 2015 version.

- ^ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2015). "Ptychocheilus lucius" in FishBase. March 2015 version.

- ^ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2015). "Paedocypris progenetica" in FishBase. March 2015 version.

- ^ Based on data sourced from the FishStat database

- ^ Magri MacMahon (1946): pp.149-152

- ^ GSMFC (2005), FFWCC [2008]

- ^ Riehl & Baensch (1996): p.410

- ^ Helfman et al. (1997): p.228

- ^ de Graaf et al. (2007), He et al. (2008a,b)

- ^ a b He et al. (2008a)

- ^ Howes (1991), de Graaf et al. (2007), IUCN (2009)

- ^ He et al. (2008b)

- ^ Tao W, Mayden RL, He S (2012) Remarkable phylogenetic resolution of the most complex clade of Cyprinidae (Teleostei: Cypriniformes): A proof of concept of homology assessment and partitioning sequence data integrated with mixed model Bayesian analyses. Mol Phylogenet Evol pii: S1055-7903(12)00381-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.09.024

- ^ a b Chang, C.-H., Li, F., Shao, K.-T., Lin, Y.-S., Morosawa, T., Kim, S., Koo, H., Kim, W., Lee, J.-S., He, S., Smith, C., Reichard, M., Miya, M., Sado, T., Uehara, K., Lavoué, S., Chen, W.-J. & Mayden, R.L. (in press): Phylogenetic relationships of Acheilognathidae (Cypriniformes: Cyprinoidea) as revealed from evidence of both nuclear and mitochondrial gene sequence variation: Evidence for necessary taxonomic revision in the family and the identification of cryptic species. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 81: 182-194.

- ^ Borkenhagen, K. (2014): A new genus and species of cyprinid fish (Actinopterygii, Cyprinidae) from the Arabian Peninsula, and its phylogenetic and zoogeographic affinities. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 97: 1179–1195.

- ^ a b Pethiyagoda, R., Meegaskumbura, M. & Maduwage, K. (2012): A synopsis of the South Asian fishes referred to Puntius (Pisces: Cyprinidae). Ichthyological Exploration of Freshwaters, 23 (1): 69-95.

- ^ a b c d Kottelat, M. (2013): The Fishes of the Inland Waters of Southeast Asia: A Catalogue and Core Bibliography of the Fishes Known to Occur in Freshwaters, Mangroves and Estuaries. The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology, 2013, Supplement No. 27: 1–663.

- ^ Pethiyagoda, R. (2013): Haludaria, a replacement generic name for Dravidia (Teleostei: Cyprinidae). Zootaxa, 3646 (2): 199.

- ^ Zhao, H.-T., Sullivan, J.P., Zhang, Y.-G. & Peng, Z.-G. (2014): Paraqianlabeo lineatus, a new genus and species of labeonine fishes (Teleostei: Cyprinidae) from South China. Zootaxa, 3841 (2): 257–270.

- ^ Zhang, E & Zhou, W. (2012): Sinigarra napoense, a new genus and species of labeonin fishes (Teleostei: Cyprinidae) from Guangxi Province, South China. Zootaxa, 3586: 17–25.

- ^ Huang, Y., Yang, J. & Chen, X. (2014): Stenorynchoacrum xijiangensis, a new genus and a new species of Labeoninae fish from Guangxi, China (Teleostei: Cyprinidae). Zootaxa, 3793 (3): 379–386.

- ^ Britz, R., Kottelat, M. & Tan, H.H. (2012): Fangfangia spinocleithralis, a new genus and species of miniature cyprinid from Kalimantan Tengah, Borneo, Indonesia (Teleostei: Cypriniformes: Cyprinidae). Ichthyological Exploration of Freshwaters, 22 (4) [2011]: 327-335.

- ^ a b Bianco, P.G., Ketmaier, V. (2014). A revision of the Rutilus complex from Mediterranean Europe with description of a new genus, Sarmarutilus, and a new species, Rutilus stoumboudae (Teleostei: Cyprinidae). Zootaxa, 3841 (3): 379–402.

Further reading[edit]

- De Graaf, Martin; Megens, Hendrik-Jan; Samallo, Johannis; Sibbing, Ferdinand A. (2007). "Evolutionary origin of Lake Tana's (Ethiopia) small Barbus species: Indications of rapid ecological divergence and speciation". Animal Biology 57: 39. doi:10.1163/157075607780002069.

- dictionary.com [2009]: Cyprinid. Retrieved 2009-SEP-25.

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2011). "Cyprinidae" in FishBase. August 2011 version.

- Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FFWCC) (2006): Florida's Exotic Freshwater Fishes. Retrieved 2007-03-05.

- Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission (GSMFC) (2005): Cyprinus carpio (Linnaeus, 1758). Version of 2005-08-03. Retrieved 2007-05-03.

- He, Shunping; Mayden, Richard L.; Wang, Xuzheng; Wang, Wei; Tang, Kevin L.; Chen, Wei-Jen; Chen, Yiyu (2008). "Molecular phylogenetics of the family Cyprinidae (Actinopterygii: Cypriniformes) as evidenced by sequence variation in the first intron of S7 ribosomal protein-coding gene: Further evidence from a nuclear gene of the systematic chaos in the family". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 46 (3): 818–29. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.06.001. PMID 18203625.

- He, Shunping; Gu, Xun; Mayden, Richard L.; Chen, Wei-Jen; Conway, Kevin W.; Chen, Yiyu (2008). "Phylogenetic position of the enigmatic genus Psilorhynchus (Ostariophysi: Cypriniformes): Evidence from the mitochondrial genome". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 47 (1): 419–25. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.10.012. PMID 18053751.

- Helfman, Gene (1997). The Diversity of Fishes. Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-86542-256-7.

- Howes, G. J. (1991): Systematics and biogeography: an overview. In: Winfield, I. J. & Nelson, J. S. (eds.): Biology of Cyprinids: 1–33. Chapman and Hall Ltd., London.

- International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) (2009): 2009 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2009.1. Retrieved 2009-SEP-20.

- Magri MacMahon, A. F. (1946): Fishlore. Pelican Books.

- Nelson, Joseph (2006). Fishes of the World. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-25031-7.

- Riehl, Rudiger (1996). Aquarium Atlas. Voyageur Press (MN). ISBN 3-88244-050-3.

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Wikipedia |

| Source | http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Cyprinidae&oldid=653239624 |

Labeoninae is a doubtfully distinct subfamily of ray-finned fishes in the family Cyprinidae of order Cypriniformes. They inhabit freshwater and the largest species richness is in the region around southern China, but there are also species elsewhere in Asia, and some members of Garra and Labeo are from Africa. They are a generally very apomorphic group, perhaps the most "advanced" of the Cyprinidae. A common name for these fishes is labeonins (when considered a distinct subfamily) or labeoins (when included in subfamily Cyprininae).

They include the group sometimes separated as Garrinae, but these do not seem to be that distinct. In fact, the entire Labeoninae is merged into the Cyprininae by a number of authors; in any case, these two and the former "Barbinae" form a close-knit group whose internal phylogeny is far from resolved. If the subfamily is considered distinct, it is typically split in the tribes Labeonini (which are able to swimm well in open water) and Garrini (which are mostly benthic), and sometimes in addition the Banganini (which are somewhat intermediate in habitus) If the labeo lineage is included in the Cyprininae, it becomes the tribe Labeonini, while its two (or three) subdivisions are the subtribes Labeoina, Garraina and perhaps Banganina.[1]

Notable genera are Crossocheilus, Epalzeorhynchos and Garra, which contain some of the popular aquarium fishes often called "algae eaters", e.g. the Siamese Algae Eater (Crossocheilus siamensis). Labeo – the type genus of this subfamily – contains many sizeable species which are often used as food.

Anatomically, the labeonins are distinguished by the Weberian apparatus contacting the skull with the supraneural bones, and its basioccipital process being concave in cross-section. The first vertebra has a parapophysis that is elongated to forward and partially overlaps the basioccipital process. The fourth vertebra, meanwhile, has a short but stout transverse process that is prominently elongated bellywards; the os suspensorium is often hidden behind if viewed from the side. In the skull, the frontal and sphenotic bones have prominent foramina. In the anal fin, the first pterygiophore is elongated and has well-developed anterior and posterior flanges, with the former very large and concave at the distal end. Most labeonins have the skinny flap of the underside of the snout well-developed into a fleshy cap that at least partially hides the upper lip except when feeding, and a similar structure at the lower lip.[2]

Genera[edit]

|

Tribe Labeonini

Tribe Banganini (might belong in Labeonini)

|

Tribe Garrini

|

The supposed genus "Tylognathus", commonly placed in the Labeonini (or Labeoina), is actually a polyphyletic assemblage containing diverse labeonins and some other cyprinids. Its type species, variously called "Tylognathus diplostoma" or "Tylognathus valenciennesii", is actually Bangana diplostoma; most of its other species are now in Lobocheilos.

Footnotes[edit]

References[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Garrinae. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Labeoninae. |

- de Graaf, Martin; Megens, Hendrik-Jan; Samallo, Johannis & Sibbing, Ferdinand A. (2007): Evolutionary origin of Lake Tana's (Ethiopia) small Barbus species: indications of rapid ecological divergence and speciation. Anim. Biol. 57(1): 39-48. doi:10.1163/157075607780002069 (HTML abstract)

- He, Shunping; Mayden, Richard L.;Wang, Xuzheng; Wang, Wei; Tang, Kevin L.; Chen, Wei-Jen & Chen, Yiyu (2008): Molecular phylogenetics of the family Cyprinidae (Actinopterygii: Cypriniformes) as evidenced by sequence variation in the first intron of S7 ribosomal protein-coding gene: Further evidence from a nuclear gene of the systematic chaos in the family. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 46(3): 818–829. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.06.001 PDF fulltext

- Stiassny, Melanie L.J. & Getahun, Abebe (2007): An overview of labeonin relationships and the phylogenetic placement of the Afro-Asian genus Garra Hamilton, 1922 (Teleostei: Cyprinidae), with the description of five new species of Garra from Ethiopia, and a key to all African species. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 150(1): 41-83. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00281.x PDF fulltext

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Wikipedia |

| Source | http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Labeoninae&oldid=628634010 |