You are here

Species

Flavivirus

IUCN

NCBI

EOL Text

Flavivirus is a genus of viruses in the family Flaviviridae. This genus includes the West Nile virus, dengue virus, tick-borne encephalitis virus, yellow fever virus, and several other viruses which may cause encephalitis.[2]

Flaviviruses are named from the yellow fever virus, the type virus for the family; the word "flavus" means "yellow" in Latin. The name "yellow fever" originated from its propensity to cause yellow jaundice in victims.[3]

Flaviviruses share several common aspects: common size (40-65 nm), symmetry (enveloped, icosahedral nucleocapsid), nucleic acid (positive-sense, single-stranded RNA of approximately 10,000–11,000 bases), and appearance in the electron microscope.

Most of these viruses are transmitted by the bite from an infected arthropod (mosquito or tick) and hence, classified as arboviruses. Human infections with these viruses are typically incidental, as humans are unable to replicate the virus to high enough titres to reinfect arthropods needed to continue the virus life cycle – man is a dead end host. The exceptions to this are yellow fever and dengue viruses, which still require mosquito vectors, but are well-enough adapted to humans as to not necessarily depend upon animal hosts (although both continue to have important animal transmission routes as well).

Other virus transmission routes for arboviruses include handling infected animal carcasses, blood transfusion, child birth and through consumption of unpasteurised milk products. The transmission from animals to humans without an intermediate vector arthropod is thought to be unlikely. For example, early tests with yellow fever showed that the disease is not contagious.

The known non-arboviruses of the flavivirus family either reproduce in arthropods or vertebrates, but not both.

Contents

Replication[edit]

Flaviviruses have a (+) sense RNA genome and replicate in the cytoplasm of the host cells. The genome mimics the cellular mRNA molecule in all aspects except for the absence of the poly-adenylated (poly-A) tail. This feature allows the virus to exploit cellular apparatus to synthesise both structural and non-structural proteins, during replication. The cellular ribosome is crucial to the replication of the flavivirus, as it translates the RNA, in a similar fashion to cellular mRNA, resulting in the synthesis of a single polyprotein. In general, the genome encodes 3 structural proteins (Capsid, prM, and Envelope) and 8 non-structural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5 and NS5B)[citation needed]. The genomic RNA is modified at the 5′ end of positive-strand genomic RNA with a cap-1 structure (me7-GpppA-me2).

Cellular RNA cap structures are formed via the action of an RNA triphosphatase, with guanylyltransferase, N7-methyltransferase and 2′-O methyltransferase. The virus encodes these activities in its non-structural proteins. The NS3 protein encodes a RNA triphosphatase within its helicase domain. It uses the helicase ATP hydrolysis site to remove the γ-phosphate from the 5′ end of the RNA. The N-terminal domain of the non-structural protein 5 (NS5) has both the N7-methyltransferase and guanylyltransferase activities necessary for forming mature RNA cap structures. RNA binding affinity is reduced by the presence of ATP or GTP and enhanced by S-adenosyl methionine.[4] This protein also encodes a 2′-O methyltransferase.

Once translated, the polyprotein is cleaved by a combination of viral and host proteases to release mature polypeptide products. Nevertheless, cellular post-translational modification is dependent on the presence of a poly-A tail; therefore this process is not host-dependent. Instead, the polyprotein contains an autocatalytic feature which automatically releases the first peptide, a virus specific enzyme. This enzyme is then able to cleave the remaining polyprotein into the individual products. One of the products cleaved is a polymerase, responsible for the synthesis of a (-) sense RNA molecule. Consequently this molecule acts as the template for the synthesis of the genomic progeny RNA.

Flavivirus genomic RNA replication occurs on rough endoplasmic reticulum membranes in membranous compartments.

New viral particles are subsequently assembled. This occurs during the budding process which is also responsible for the accumulation of the envelope and cell lysis.

A G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (also known as ADRBK1) appears to be important in entry and replication for several Flaviviridae.[5]

RNA secondary structure elements[edit]

| Flavivirus 3'UTR stem loop IV | |

|---|---|

|

|

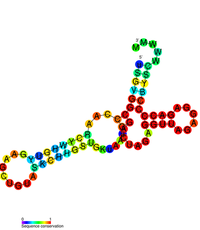

| Predicted secondary structure of the Flavivirus 3'UTR stem loop IV | |

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | Flavivirus_SLIV |

| Rfam | RF01415 |

| Other data | |

| RNA type | Cis-reg |

| Domain(s) | Flaviviridae |

| SO | 0005836 |

| Flavivirus DB element | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Predicted secondary structure of the Flavivirus DB element | |

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | Flavivirus_DB |

| Rfam | RF00525 |

| Other data | |

| RNA type | Cis-reg |

| Domain(s) | Flaviviridae |

| SO | 0000233 |

| Flavivirus 3' UTR cis-acting replication element (CRE) | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Predicted secondary structure of the Flavivirus 3' UTR cis-acting replication element (CRE) | |

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | Flavi_CRE |

| Alt. Symbols | Flavi_pk3 |

| Rfam | RF00185 |

| Other data | |

| RNA type | Cis-reg |

| Domain(s) | Flaviviridae |

| SO | 0000205 |

| Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) hairpin structure | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Predicted secondary structure of the Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) hairpin structure | |

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | JEV_hairpin |

| Rfam | RF00465 |

| Other data | |

| RNA type | Cis-reg |

| Domain(s) | Flaviviridae |

| SO | 0000233 |

The (+) sense RNA genome of Flavivirus contains 5' and 3' untranslated regions (UTRs).

5'UTR[edit]

The 5'UTRs are 95–101 nucleotides long in Dengue virus.[6] There are two conserved structural elements in the Flavivirus 5'UTR, a large stem loop (SLA) and a short stem loop (SLB). SLA folds into a Y-shaped structure with a side stem loop and a small top loop.[6][7] SLA is likely to act as a promoter, and is essential for viral RNA synthesis.[8][9] SLB is involved in interactions between the 5'UTR and 3'UTR which result in the cyclisation of the viral RNA, which is essential for viral replication.[10]

3'UTR[edit]

The 3'UTRs are typically 0.3–0.5 kb in length and contain a number of highly conserved secondary structures which are conserved and restricted to the flavivirus family. The majority of analysis has been carried out using West Nile virus (WNV) to study the function the 3'UTR.

Currently 8 secondary structures have been identified within the 3'UTR of WNV and are (in the order in which they are found with the 3'UTR) SL-I, SL-II, SL-III, SL-IV, DB1, DB2 and CRE.[11][12] Some of these secondary structures have been characterised and are important in facilitating viral replication and protecting the 3'UTR from 5' endonuclease digestion. Nuclease resistance protects the downstream 3' UTR RNA fragment from degradation and is essential for virus-induced cytopathicity and pathogenicity.

- SL-II

SL-II has been suggested to contribute to nuclease resistance.[12] It may be related to another hairpin loop identified in the 5'UTR of the Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) genome.[13] The JEV hairpin is significantly over-represented upon host cell infection and it has been suggested that the hairpin structure may play a role in regulating RNA synthesis.

- SL-IV

This secondary structure is located within the 3'UTR of the genome of Flavivirus upstream of the DB elements. The function of this conserved structure is unknown but is thought to contribute to ribonuclease resistance.

- DB1/DB2

These two conserved secondary structures are also known as pseudo-repeat elements. They were originally identified within the genome of Dengue virus and are found adjacent to each other within the 3'UTR. They appear to be widely conserved across the Flaviviradae. These DB elements have a secondary structure consisting of three helices and they play a role in ensuring efficient translation. Deletion of DB1 has a small but significant reduction in translation but deletion of DB2 has little effect. Deleting both DB1 and DB2 reduced translation efficiency of the viral genome to 25%.[11]

- CRE

CRE is the Cis-acting replication element, also known as the 3'SL RNA elements, and is thought to be essential in viral replication by facilitating the formation of a "replication complex".[14] Although evidence has been presented for an existence of a pseudoknot structure in this RNA, it does not appear to be well conserved across flaviviruses.[15] Deletions of the 3' UTR of flaviviruses have been shown to be lethal for infectious clones.

Conserved hairpin cHP[edit]

A conserved hairpin (cHP) structure was later found in several Flavivirus genomes and is thought to direct translation of capsid proteins. It is located just downstream of the AUG start codon.[16]

Evolution[edit]

The flaviviruses can be divided into 2 clades: one with the vector borne viruses and the other with no known vector.[17] The vector clade can be subdivided into a mosquito borne clade and a tick borne clade. These groups can be divided again.[18]

The mosquito group can be divided into two branches: one branch contains the neurotropic viruses, often associated with encephalitic disease in humans or livestock. This branch tends to be spread by Culex species and to have bird reservoirs. The second branch is the non-neurotropic viruses which are associated with haemorrhagic disease in humans. These tend to have Aedes species as vectors and primate hosts.

The tick-borne viruses also form two distinct groups: one is associated with seabirds and the other - the tick-borne encephalitis complex viruses - is associated primarily with rodents.

The viruses that lack a known vector can be divided into three groups: one closely related to the mosquito-borne viruses which is associated with bats; a second, genetically more distant, is also associated with bats; and a third group is associated with rodents.

It seems likely that tick transmission may have been derived from a mosquito borne group.[19]

Species[edit]

Tick-borne viruses[edit]

- Mammalian tick-borne virus group

- Absettarov virus

- Alkhurma virus (ALKV)

- Deer tick virus (DT)

- Gadgets Gully virus (GGYV)

- Kadam virus (KADV)

- Karshi virus

- Kyasanur Forest disease virus (KFDV)

- Langat virus (LGTV)

- Louping ill virus (LIV)

- Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus (OHFV)

- Powassan virus (POWV)

- Royal Farm virus (RFV)

- Sokuluk virus (SOKV)

- Tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV)

- Turkish sheep encephalitis virus (TSE)

- Seabird tick-borne virus group

- Kama virus (KAMV)

- Meaban virus (MEAV)

- Saumarez Reef virus (SREV)

- Tyuleniy virus (TYUV)

Mosquito-borne viruses[edit]

- Without known vertebrate host

- Aedes flavivirus

- Barkedji virus

- Calbertado virus

- Cell fusing agent virus

- Chaoyang virus

- Culex flavivirus

- Culex theileri flavivirus

- Donggang virus

- Ilomantsi virus

- Kamiti River virus

- Lammi virus

- Marisma mosquito virus

- Nakiwogo virus

- Nhumirim virus

- Nounane virus

- Spanish Culex flavivirus

- Spanish Ochlerotatus flavivirus

- Quang Binh virus

- Aroa virus group

- Aroa virus (AROAV)

- Bussuquara virus

- Dengue virus group

- Dengue virus (DENV)

- Kedougou virus (KEDV)

- Japanese encephalitis virus group

- Bussuquara virus

- Cacipacore virus (CPCV)

- Koutango virus (KOUV)

- Ilheus virus (ILHV)

- Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV)

- Murray Valley encephalitis virus (MVEV)

- Rocio virus (ROCV)

- St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV)

- Usutu virus (USUV)

- West Nile virus (WNV)

- Yaounde virus (YAOV)

- Kokobera virus group

- Kokobera virus (KOKV)

- Ntaya virus group

- Bagaza virus (BAGV)

- Baiyangdian virus (BYDV)

- Duck egg drop syndrome virus (BYDV)

- Ilheus virus (ILHV)

- Jiangsu virus (JSV)

- Israel turkey meningoencephalomyelitis virus (ITV)

- Ntaya virus (NTAV)

- Tembusu virus (TMUV)

- Spondweni virus group

- Zika virus (ZIKV)

- Yellow fever virus group

- Banzi virus (BANV)

- Bouboui virus (BOUV)

- Edge Hill virus (EHV)

- Jugra virus (JUGV)

- Saboya virus (SABV)

- Sepik virus (SEPV)

- Uganda S virus (UGSV)

- Wesselsbron virus (WESSV)

- Yellow fever virus (YFV)

Viruses with no known arthropod vector[edit]

- Entebbe virus group

- Entebbe bat virus (ENTV)

- Yokose virus (YOKV)

- Modoc virus group

- Apoi virus (APOIV)

- Cowbone Ridge virus (CRV)

- Jutiapa virus (JUTV)

- Modoc virus (MODV)

- Sal Vieja virus (SVV)

- San Perlita virus (SPV)

- Rio Bravo virus group

- Bukalasa bat virus (BBV)

- Carey Island virus (CIV)

- Dakar bat virus (DBV)

- Montana myotis leukoencephalitis virus (MMLV)

- Phnom Penh bat virus (PPBV)

- Rio Bravo virus (RBV)

Non vertebrate viruses[edit]

Viruses known only from sequencing[edit]

Vaccines[edit]

The successful yellow fever 17D vaccine, introduced in 1937, produced dramatic reductions in epidemic activity. Effective killed Japanese encephalitis and Tick-borne encephalitis vaccines were introduced in the middle of the 20th century. Unacceptable adverse events have prompted change from a mouse-brain killed Japanese encephalitis vaccine to safer and more effective second generation Japanese encephalitis vaccines. These may come into wide use to effectively prevent this severe disease in the huge populations of Asia - North, South and Southeast. The dengue viruses produce many millions of infections annually due to transmission by a successful global mosquito vector. As mosquito control has failed, several dengue vaccines are in varying stages of development. A tetravalent chimeric vaccine that splices structural genes of the four dengue viruses onto a 17D yellow fever backbone is in Phase III clinical testing.[2]

References[edit]

- ^ International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (20 March 2010). "ICTV 2009 Master Species List Version 4".

- ^ a b Shi, P-Y (editor) (2012). Molecular Virology and Control of Flaviviruses. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-92-9.

- ^ The earliest mention of "yellow fever" appears in a manuscript of 1744 by Dr. John Mitchell of Virginia; copies of the manuscript were sent to Mr. Cadwallader Colden, a physician in New York, and to Dr. Benjamin Rush of Philadelphia; the manuscript was eventually reprinted in 1814. See:

(Dr. John Mitchell) (written: 1744 ; reprinted: 1814) "Account of the Yellow fever which prevailed in Virginia in the years 1737, 1741, and 1742, in a letter to the late Cadwallader Colden, Esq. of New York, from the late John Mitchell, M.D.F.R.S. of Virginia," American Medical and Philosophical Register … , 4 : 181-215. The term "yellow fever" appears on p. 186. On p. 188, Mitchell mentions "… the distemper was what is generally called the yellow fever in America." However, on pages 191-192, he states "… I shall consider the cause of the yellowness which is so remarkable in this distemper, as to have given it the name of the Yellow Fever."

It should be noted, however, that Dr. Mitchell misdiagnosed the disease that he observed and treated, and that the disease was probably Weil's disease or hepatitis. See: Saul Jarcho (1957) "John Mitchell, Benjamin Rush, and Yellow fever," Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 31 (2) : 132-6. - ^ Henderson BR, Saeedi BJ, Campagnola G, Geiss BJ (2011). Jeang, K.T, ed. "Analysis of RNA binding by the Dengue virus NS5 RNA capping enzyme". PLoS ONE 6 (10): e25795. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...625795H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025795.

- ^ Le Sommer C, Barrows NJ, Bradrick SS, Pearson JL, Garcia-Blanco MA (2012). Michael, Scott F, ed. "G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 promotes flaviviridae entry and replication". PLoS Negl Trop Dis 6 (9): e1820. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001820.

- ^ a b Gebhard LG, Filomatori CV, Gamarnik AV (2011). "Functional RNA elements in the dengue virus genome". Viruses 3 (9): 1739–56. doi:10.3390/v3091739. PMC 3187688. PMID 21994804.

- ^ Brinton MA, Dispoto JH (1988). "Sequence and secondary structure analysis of the 5'-terminal region of flavivirus genome RNA". Virology 162 (2): 290–9. doi:10.1016/0042-6822(88)90468-0. PMID 2829420.

- ^ Filomatori CV, Lodeiro MF, Alvarez DE, Samsa MM, Pietrasanta L, Gamarnik AV (2006). "A 5' RNA element promotes dengue virus RNA synthesis on a circular genome". Genes Dev 20 (16): 2238–49. doi:10.1101/gad.1444206. PMC 1553207. PMID 16882970.

- ^ Yu L, Nomaguchi M, Padmanabhan R, Markoff L (2008). "Specific requirements for elements of the 5' and 3' terminal regions in flavivirus RNA synthesis and viral replication". Virology 374 (1): 170–85. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2007.12.035. PMC 3368002. PMID 18234265.

- ^ Alvarez DE, Lodeiro MF, Ludueña SJ, Pietrasanta LI, Gamarnik AV (2005). "Long-range RNA-RNA interactions circularize the dengue virus genome". J Virol 79 (11): 6631–43. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.11.6631-6643.2005. PMC 1112138. PMID 15890901.

- ^ a b Chiu WW, Kinney RM, Dreher TW (July 2005). "Control of Translation by the 5′- and 3′-Terminal Regions of the Dengue Virus Genome". J. Virol. 79 (13): 8303–15. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.13.8303-8315.2005. PMC 1143759. PMID 15956576.

- ^ a b Pijlman GP, Funk A, Kondratieva N, et al. (December 2008). "A highly structured, nuclease-resistant, noncoding RNA produced by flaviviruses is required for pathogenicity". Cell Host Microbe 4 (6): 579–91. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2008.10.007. PMID 19064258.

- ^ Lin KC, Chang HL, Chang RY (May 2004). "Accumulation of a 3′-Terminal Genome Fragment in Japanese Encephalitis Virus-Infected Mammalian and Mosquito Cells". J. Virol. 78 (10): 5133–8. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.10.5133-5138.2004. PMC 400339. PMID 15113895.

- ^ Zeng L, Falgout B, Markoff L (September 1998). "Identification of Specific Nucleotide Sequences within the Conserved 3′-SL in the Dengue Type 2 Virus Genome Required for Replication". J. Virol. 72 (9): 7510–22. PMC 109990. PMID 9696848.

- ^ Shi PY, Brinton MA, Veal JM, Zhong YY, Wilson WD (April 1996). "Evidence for the existence of a pseudoknot structure at the 3' terminus of the flavivirus genomic RNA". Biochemistry 35 (13): 4222–30. doi:10.1021/bi952398v. PMID 8672458.

- ^ Clyde K, Harris E; (2006). "RNA Secondary Structure in the Coding Region of Dengue Virus Type 2 Directs Translation Start Codon Selection and Is Required for Viral Replication". J Virol 80 (5): 2170–2182. doi:10.1128/JVI.80.5.2170-2182.2006. PMC 1395379. PMID 16474125.

- ^ Kuno G, Chang GJ, Tsuchiya KR, Karabatsos N, Cropp CB (1998). "Phylogeny of the genus Flavivirus". J Virol 72 (1): 73–83. PMC 109351. PMID 9420202.

- ^ Gaunt MW, Sall AA, de Lamballerie X, Falconar AK, Dzhivanian TI, Gould EA (2001). "Phylogenetic relationships of flaviviruses correlate with their epidemiology, disease association and biogeography". J Gen Virol 82 (8): 1867–1876.

- ^ Cook S, Holmes EC (2006). "A multigene analysis of the phylogenetic relationships among the flaviviruses (Family: Flaviviridae) and the evolution of vector transmission". Arch Virol 151 (2): 309–325. doi:10.1007/s00705-005-0626-6. PMID 16172840.

- Kuno G, Chang GJ, Tsuchiya KR, Karabatsos N, Cropp CB (Jan 1998). "Phylogeny of the genus Flavivirus". J Virol 72 (1): 73–83. PMC 109351. PMID 9420202.

- Zanotto PM; Gould, Ernest A.; Gao, George F.; Harvey, Paul H.; Holmes, Edward C. (Jan 1996). "Population dynamics of flaviviruses revealed by molecular phylogenies". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 93 (2): 548–53. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93..548Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.2.548. PMC 40088. PMID 8570593.

- Molecular Biology of the Flavivirus. - Matthias Kalitzky, Taylor & Francis Ltd 2005 Oct 5; ISBN 1-904933-22-X

- Molecular Virology and Control of Flaviviruses. - Pei-Yong Shi, Caister Academic Press; ISBN 978-1-904455-92-9

- Architects of Assembly: roles of Flaviviridae nonstructural proteins in virion morphogenesis. -Catherine L. Murray, Christopher T. Jones, and Charles M. Rice | PMCID: PMC2764292

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Wikipedia |

| Source | http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Flavivirus&oldid=638652455 |

Alkhumra virus (ALKV) is a member of the Flaviviridae virus family (class IV).

§Taxonomy[edit]

It is closely related to the Kyasanur Forest disease virus (KFDV) with which it shares 89% nucleotide sequence homology.[1] It appears that these viruses diverged 700 years ago.[2]

Related viruses include Karshi virus and Farm Royal virus.

§Clinical[edit]

This virus[3] was first isolated in Saudi Arabia in the 1990s and since then there have been 24 reported cases, mainly occurring among butchers, with the case fatality-rate above 30%. It was first discovered in the blood of 6 male butchers, aged 24–39 years, in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia in November and December 1995. It causes a type of tick-borne hemorrhagic fever with the symptoms including fever, headache, joint pain, muscle pain, vomiting and thrombocytopenia which lead to hemorrhagic fever and encephalitis which can result in death.[4]

§Epidemiology[edit]

Camels and sheep are the natural hosts of this virus but it is not yet known if other mammals are also involved in its life cycle. There appears to be more than one possible route of transmission seen in people who have become infected with this virus. These are a bite by an infected tick, ingestion of unpasteurised camel milk or entry via a skin wound.

The geographic distribution of the virus may extend beyond Saudi Arabia; it has been imported to other countries in travelers from an area not known to be endemic for the disease.[5] A Saudi study published in December 2011 provided evidence for a wider range of endemicity than previously reported, with most seropositive persons originating from Tabouk and Eastern Directorates.[6]

§References[edit]

- ^ Deresinski S (2010) Alkhurma Hemorrhagic Fever Virus: An Emerging Pathogen. Clinical Infectious Diseases 51(4): iv, http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/51/4/iv.full.

- ^ Dodd KA, Bird BH, Khristova ML, Albariño CG, Carroll SA, Comer JA, Erickson BR, Rollin PE, Nichol ST (2011) Ancient ancestry of KFDV and AHFV revealed by complete genome analyses of viruses isolated from ticks and mammalian hosts. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 5(10):e1352.

- ^ Sometimes misidentified as "Al-Khumra" virus—"It’s Al-Khurma, not Al-Khumra, says official", The Saudi Gazette, 13 Jan 2010, http://www.saudigazette.com.sa/index.cfm?method=home.regcon&contentID=2010011360023.

- ^ Zaki AM (1997). "Isolation of a flavivirus related to the tick-borne encephalitis complex from human cases in Saudi Arabia". Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 91 (2): 179–81. doi:10.1016/S0035-9203(97)90215-7. PMID 9196762.

- ^ Carletti F, Castilletti C, Di Caro A, Capobianchi MR, Nisii C, Suter F, et al. (2010) Alkhurma hemorrhagic fever in travelers returning from Egypt, 2010. Emerging Infectious Diseases, December 2010, http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1612101092.

- ^ Memish ZA, Albarrak A, Almazroa MA, Al-Omar I, Alhakeem R, Assiri A, et al. Seroprevalence of Alkhurma and other hemorrhagic fever viruses, Saudi Arabia. Emerging Infectious Diseases, December 2011, http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1712.110658.

§Further reading[edit]

- Charrel RN, Zaki AM, Fakeeh M et al. (2005). "Low diversity of Alkhurma hemorrhagic fever virus, Saudi Arabia, 1994-1999". Emerging Infect. Dis. 11 (5): 683–8. doi:10.3201/eid1105.041298. PMC 3320364. PMID 15890119.

- Charrel RN, Zaki AM, Attoui H et al. (2001). "Complete coding sequence of the Alkhurma virus, a tick-borne flavivirus causing severe hemorrhagic fever in humans in Saudi Arabia". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 287 (2): 455–61. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2001.5610. PMID 11554750.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Wikipedia |

| Source | http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Alkhurma_virus&oldid=650860118 |

| This article may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in the German Wikipedia. (October 2012) Click [show] on the right to read important instructions before translating.

|

Gadgets Gully virus (GGYV) is an arbovirus, a member of the flavivirus family first isolated from the hard tick Ixodes uriae,[1] and named after Gadget's Gully. The virus antibodies were found in several species of penguin and antibodies were found in humans. It is believed that some species of seabird forms a natural reservoir of the virus.

References [edit]

- ^ Humphrey-Smith et al. (1991). "Seroepidemiolgy of arboviruses among seabirds and island residents of the Great Barrier Reef and the Coral Sea". Epidemiology and Infection 107: 435–440.

| This virus-related article is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it. |

| License | http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ |

| Rights holder/Author | Wikipedia |

| Source | http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Gadgets_Gully_virus&oldid=557860932 |